To most, I looked like a grungy college kid. A fair estimation for a twenty-one year old wearing a hoodie and sweatpants, while standing on the fifty yard line observing spring practice. To my left stood another man in comfortable wear, but he was of a bigger stature. Both physically and mentally. He could boast, [...]

To most, I looked like a grungy college kid. A fair estimation for a twenty-one year old wearing a hoodie and sweatpants, while standing on the fifty yard line observing spring practice. To my left stood another man in comfortable wear, but he was of a bigger stature. Both physically and mentally.

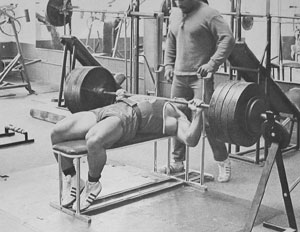

He could boast, if he were of the boasting kind, of a four-hundred-and-five pound bench press and an even more impressive, yet less concrete, squat. Six-hundred-some, perhaps? I never did care to ask. I just knew it was “big enough” and done without syringes and suits.

If I were apt to say it at the time, he certainly would have been my mentor. As the assistant coach of physical preparation he was always willing to help eager souls that wanted to learn from him. Part of me thinks it was because he knew everyone that walked through the doors leave as different person. This isn’t such an egregious estimation because, well, everyone that I knew did walk out of there that way.

I’m grateful for just about everything the experience entailed. Grateful to have observed how he trained himself. Grateful to have seen and learned how he trained his athletes. Grateful to have watched how he interacted and motivated. Grateful to have had someone answer my constant barrage of questions.

Grateful to have stood on the fifty yard line next to someone I had so much respect for.

So when he asked me what I thought of my experience thus far, I was a little taken. Originally, there were a lot of things that had caught my attention. The “half” squats. The lack of overhead pressing. The emphasis on aerobic development.

But I took my time to formulate my answer. Despite, at first, seeing things I wasn’t prepared to see, it all had a common thread: everything had strong purpose.

Notice I said strong purpose, not just purpose. I’m not talking, “well I saw X coach do it,” or, “Y coach told me so,” kind of purpose. I’m talking purpose that could be rationalized on the spot.

Even more impressive was how each element of preparation was meticulously planned. It was like he was playing Tetris and placing the blocks as if he knew the next five blocks in que.

I think he knew that the interns were seeing something that they didn’t expect at first. Something that they didn’t quite trust. Until, of course, they all—including myself—were proved wrong.

*

There was three-hundred-and-five pounds on the bar. He had already blasted past his previous max of two-hundred-and-seventy-five. Impressive considering he had a wrist injury that kept him out of bench press training for a bit.

As the spotter, I helped the athlete lift the bar from the rack, even though with the ease of the lift’s completion, it probably wasn’t necessary. James was watching, smirking. He was like a mad scientist marveling his creation that, for all intents and purposes, had exceeded expectations even though he knew it was going to. It always did.

The athlete topped out at three-hundred-and-twenty pounds. It was a forty-five pound increase in his max after training with loads primarily in the seventy percent range. I’m not going to tell you how long the training cycle was because you wouldn’t believe me anyway.

*

I tell you this story because it exposes every problem that you have, but more importantly, your failure to put purpose into your actions. I can assure you that James didn’t use any high tech gadgets or fancy exercises. No one threw up from gut wrenching intensity. Yet there was consistent improvement.

Take a look at everything you do, and question every piece of it. If you can’t answer the simplest question, “why am I doing this,” then either don’t do it or find out why you should do it. This goes for warm-ups, stretches, exercises, and even silly traditions that affect your health that have trickled with you through your life.

Why do you hit the snooze button six times before waking? Why are you doing barbell complexes? Why are you sprinting? Where does all of this stuff fit into where it is that you want to be and what you want to achieve?

I have a good question for a lot of people that are sport training: why are you squatting and deadlifting? Now, it’s not to say that doing both are bad. But you have to be able to tell yourself why you are doing both, and your answer has to make sense. If you’re a football player and your answer is, “because powerlifters do it,” then you’re on the wrong boat.

Overall, we tend to overdo everything. We bring fifteen extra appliances with us when we go camping or travelling. We buy that shirt that looks kind of cool even though we have 30 shirts, half of which are worn maybe three times per year.

Everything is more more more more. But remember that most of our success is only a result of a fraction of our work. There’s a 10%, that’s actually closer to 20%, window of “junk.” If you can find the junk and get rid of it you will be happier. The easiest way to do this is by tossing those things that you can’t rationalize.

Instead of adding on a whim ask yourself what you can do to make yourself more efficient, and make sure everything has purpose. This is the most important thing. If what you’re doing has purpose, then you’ll enjoy doing it and it will be much more purposeful.

So ask yourself what you need to do to hit your goals, and start doing it. Don’t add more, unless you’re adding purpose. As Bruce Lee said, “The height of cultivation always runs to simplicity.”