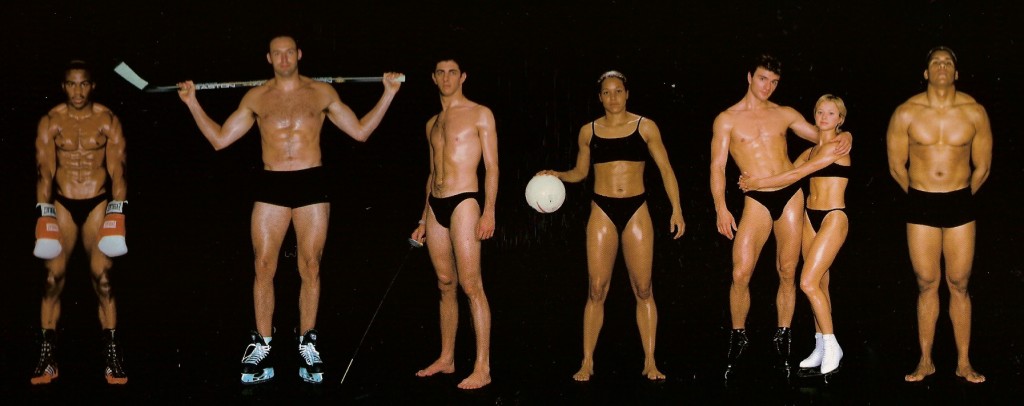

It only takes one look at a lineup of athletes from different sports to realize they all come in different shapes and sizes. This reassures me of two things. First, different body types exist. Even though somatotypes were created for psychological purposes, people do have different proportions. Not everyone follows the same rules. (This is a [...]

It only takes one look at a lineup of athletes from different sports to realize they all come in different shapes and sizes. This reassures me of two things.

First, different body types exist. Even though somatotypes were created for psychological purposes, people do have different proportions. Not everyone follows the same rules. (This is a shout out to the Skinny-Fat Brohirrim.)

Second, the theory of muscular imbalances is a crapshoot.(This may sound odd as I just hinted to contributing to this year’s Muscle Imbalances Revealed product in my post about correct “feel” for the barbell row. But allow me to explain.) In the past, I was more vehement about this. Some of the first articles ever written for this here blog were about muscular imbalances.

- Can Correcting Strength Imbalances Cause Injury? Part I

- Can Correcting Strength Imbalances Cause Injury? Part II

- Can Correcting Strength Imbalances Cause Injury? Part III

- Strength Imbalances Put to Rest – Why Great Athletes are Imbalanced

To this day, I still don’t give much credence to the idea that there’s an ideal ratio to be had among muscles. When athletes are as diverse as they are, it just can’t be possible in my opinion.

An opinion which is backed by some notes of interest.

DEBUNKING MUSCULAR IMBALANCES

The crossover effect, for example, is one reason why I think the body is smart enough to prevent itself from growing wildly out of proportion to the point of danger. Train one arm in isolation and the other arm gets stronger. That’s the crossover effect.

Another reason is that of general organism strength—the theory that all training recruits a certain percentage of motor units in relation to the body’s entire pool, and the amount and extent of those recruited affects the organism as a whole.

Consider baseball players, specifically the amount of “unbalanced” rotational work they do in both hitting and throwing. Now, there are injuries in baseball, but not as many as you would think given the volume of “unbalanced training” their body is exposed to. They play 162 games from April until September, not counting spring training or playoffs. Most games involve maximal sprinting, maximal rotational swinging, and maximal throwing.

Fun fact: Chipper Jones—arguably one of the best switch hitters of all time—said hitting from both sides of the plate may have made him more susceptible to injury.

IT’S NOT ABOUT MUSCULAR IMBALANCES

At first glance, my methods can be confused muscular imbalance theories. But saying muscular imbalances exist assumes that there’s a hidden blueprint of the body. (Holy Grail, anyone?)

At first glance, my methods can be confused muscular imbalance theories. But saying muscular imbalances exist assumes that there’s a hidden blueprint of the body. (Holy Grail, anyone?)

Every sport and every athlete has a different blueprint. What’s ideal for a center fielder won’t be ideal for a pitcher. What’s ideal for a goalie won’t be ideal for a gymnast.

Consider the differences between athletes that live around the same equipment: Olympic Weightlifters and Powerlifters. Both throw around heavy barbells and yet there’s just something “different” about the two groups of athletes. Upon testing, you would find a lot of strength differences between the two groups because the body adapts to survive, and each sport triggers different survival responses in the body.

I think (notice I’m using the word “think” here as nothing is really “proven”) most muscular imbalance problems are misinterpretations of two things:

- Big muscles being generators

- Small muscles being points of connectedness

BIG MUSCLES ARE GENERATORS

The bigger the muscle, more involved it should be in any given movement.

Crazy idea, right?

The hip houses the biggest muscles. As you get further away, the muscles get smaller and smaller.

The big muscles are generators. The golf swing, the baseball swing, the vertical jump, the sprint, and a host of other movements rely primarily on the big muscles of the hip.

This makes it seem like a muscle’s importance declines if it’s further from the center of the body. But this assumption ignores something I like to call “points of connectedness.”

Generators are only useful if they can be connected to something to give power to. So their usefulness depends on this connection.

In something like the vertical jump, the hips are the generator. The foot and ankle complex is the point of connectedness. If this connection isn’t up to par, not all generator power will be realized.

This may be easier to understand with an Olympic Weightlifting analogy. They artificially “enhance” their point of connectedness to the ground with weightlifting shoes, making for more efficient force transfer. They also enhance their point of connectedness to the bar with the hook grip.

When you look at the construction of the body, it goes like this:

- Generator (Hips, torso, shoulders)

- Link (elbows, knee)

- Point of connectedness (ankle/foot, hand/wrist)

In both the upper and lower body, the links (elbows and knees) function similarly. They don’t do much other than flex and extend. (The knee does rotate some and have a bit more freedom.) But they link the generator and point of connection.

If either the generator or point of connectedness is askew, the link will also be askew. The classic example for this is elbow problems.

CHIN-UPS AND ELBOW TENDONITIS

Elbow tendonitis is common amidst those that do a lot of straight bar work, specifically chin-ups and curls.

The fix is nearly always to opt for a neutral grip because the supinated grip ruins the natural neutral relationship between the wrist and shoulder. The elbow didn’t do anything wrong. It was just along for the ride.

Not that I haven’t used baseball enough for examples, but you will often hear of great hitters having either fast or strong wrists and either fast or strong hips. Rarely does anyone tout about “immaculate elbows” or “kick ass knees.”

The reason I was able to conquer crepitus and years of chronic knee pain was because I abided by one equation:

Hips + Feet = Knees

(In terms of health in relation to movement.)

We used to live in a knee-centric world. It was all about quads and hammies. While some of these muscles cross the hip, they aren’t the dominant muscles of the hip.

Things have changed. I’d say that we’re currently living in a glute-centric world. When ESPN writes a gigantic story about glutes, you know something is up.

But it’s only a matter of time before we begin to focus on the foot. Truly, the only reason I’m respecting and understanding the power of the foot is because I shattered mine to bits. As of now, I’m still rehabilitating it (1.5 years after breaking it), and I’m just beginning to realize the importance of isometric strength in the calves and the importance of dorsiflexion potential.

But it’s only a matter of time before we begin to focus on the foot. Truly, the only reason I’m respecting and understanding the power of the foot is because I shattered mine to bits. As of now, I’m still rehabilitating it (1.5 years after breaking it), and I’m just beginning to realize the importance of isometric strength in the calves and the importance of dorsiflexion potential.

A lot of tricksters float across the ground, subtly bouncing in between moves. I want to say that the saying having “pep in your step” is code for “diesel isometric strength in the forefoot.”

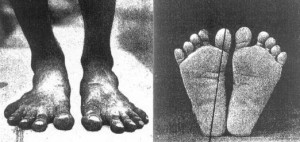

My right foot is a lot more “locked up” than it used to be. My toes overlap and come to more of a point than compared to my left. It’s a shame that 6-8 weeks in a cast does these sorts of things. My current plan is to destroy myself with a lacrosee ball in hopes of “making space” by separating the joints in my foot.

You would be surprised at the kind of difference a wider base makes—something I realized during handstands. The narrower the fingers, the more my wrists, elbows, and shoulders got hurt. The more I splayed my fingers (to a reasonable extent), the more control I had which led to less injuries.

You would be surprised at the kind of difference a wider base makes—something I realized during handstands. The narrower the fingers, the more my wrists, elbows, and shoulders got hurt. The more I splayed my fingers (to a reasonable extent), the more control I had which led to less injuries.

All things being equal, movement, balance, everything should be easier from a wider base. Most people are walking around on stilts because of the way their foot has contorted over time to fit into shoes. But I want to say the foot should fan. The more separation you have in between your big and second toe the better.

PUTTING INTO ALL TOGETHER INTO ATHLETIC MOVEMENT

As wacky as it seems, this relates to things as seemingly trivial as the barbell row. If your “feeling” the row in the wrong places, you’re wiring is likely out of whack. And if you’re wiring is out of whack, your foundation for athletic movement is likely out of whack too.

So if you want to play electrician, here’s some of my secret sauce. Use it as a launch pad.

1. Stretch the hip flexors, but stretch them correctly. This is a given in our age, but most people don’t stretch the hip flexors right. The trailing leg should be internally rotated with the toes flexed and pressed against the ground. Cross your hands behind your head and lean to the opposite side of whichever leg is being stretched. Or you can just do the super stretch shown above.

2. Find your forefoot. You can do something like front squat (or regular) calf raises, but don’t let the heel touch the ground. Teach your lower leg how to balance the body. Alternatively, you can load up a barbell, throw it on your back, and simply walk around on your tip toes.

I can’t say this is going to turn you into the next Michael Jordan, but that isometric strength is going to help you develop a better connection between your foot and the ground.

“…if calf muscles are not the most important contributors to a high vertical jump, in any case, they are important because in the execution of vertical jump they are involved as organic part of explosive legs extension movements in the last part of push up phase.

The calf rises are not the main exercise for the vertical jump height increasing but they cannot be eliminated in the training program.

Calf rise is the training mean that assures the increasing of calf muscles strength. The preliminary increasing of maximal strength of calf muscles is needed to assure the subsequent increasing of their explosive strength, starting strength and reactive ability.

Calf muscles are strongly involved in the lending shock absorbing phase of run and bounces. The preliminary enforcement of calf muscles, before the use of jumping exercises, it’s needed also to avoid legs injuries (calf muscles strain).

– YuriVerkhoshansky

3. Get your hips firing.

Getting the hips to fire was undoubtedly one of the most significant moments of my training career. And that’s if you want to consider a year’s worth of hard work a “moment.” It’s taken me from knee pain to knee health. Squat woes to squat triumphs. Hell, it even fixed my barbell row. (Remember, rewiring stems deep and infests more than one specific movement pattern. There’s also a general aspect to it.)

Crazily enough, it also broke my foot because I was flying through the roof during a tricking session. My moves were so high that I was seriously missing the ground on my landings, to the point of them just looking ugly because of how surprised I was. My body wasn’t going where I was used to it going because I had extra airtime.

Lo and behold, body parts ended up in wrong places, and I ended up with a cast around my leg. So let’s not forget increased the ability of the hips to increase vertical jumping power.

But before I get into how to fix the hips, I want you to digest everything else first, as the the overall scheme of motor programming and patterning can get rather complex.

+++++

Check back on Tuesday for more goodies. And be sure to ask your questions in the interim. The comment boxes are below. It’s always a jammin’ place down there, so join the party.