If you’re trying to lose fat and build muscle, you probably know a thing or two about energy and calories. Or maybe you don’t, in which case you need to read Part 1. If you’re too lazy to read Part 1, the following recap’ll have to do. Your body needs energy. You’re using energy 24/7. [...]

If you’re trying to lose fat and build muscle, you probably know a thing or two about energy and calories. Or maybe you don’t, in which case you need to read Part 1.

If you’re too lazy to read Part 1, the following recap’ll have to do.

- Your body needs energy.

- You’re using energy 24/7.

- You get energy from food.

- Energy is measured in calories.

- There’s intake and output.

- Output > Intake = Deficit/Loss

- Intake > Output = Surplus/Gain

Sounds good.

But its shit.

For two reasons.

The first reason is the sexier of the two, which is exactly why I’m saving it for later. Grandma’s rule. So let’s start with the second reason. (I hate myself.)

Introducing: counting calories

Energy balance dictates body composition through the “rules” listed above.

- Output > Intake = Deficit/Loss

- Intake > Output = Surplus/Gain

For all intents and purposes, we can say that, if you’re using the “rules” above, you’re using a strategy known as “counting calories.”

Counting calories entails (a) finding out how many calories you burn in a given day, and then (b) finding out how many calories you eat in a given day.

You then use the “rules” above to hack the system.

- If you want to gain weight, you make sure you’re eating more than what you need.

- If you want to lose weight, you make sure you’re eating less than what you need.

This is the same concept I established at the end of Part 1, I’m just giving the art itself a name for easy reference.

Counting calories: truth versus practicality

Forget about the “rules” supporting the calorie counting infrastructure. Instead, look at the practicality. Counting calories is only a viable strategy if you can do two things:

- Reliably calculate daily energy output.

- Reliably calculate daily energy intake.

You HAVE to be able to do these two things and get reliable values for each, otherwise you’re playing a game of chess against an opponent using invisible pieces.

If you think you’re eating 2000 calories per day, but you’re actually eating 3000 calories per day, you’ve got some problems. Likewise, if you think you’re burning 3000 calories per day, but you’re actually burning 2000 calories per day, you’ve got some problems. So this whole “data reliability” issue is something to look into.

No big deal. Lots of people would say you can reliably calculate your daily energy intake and your daily energy output. People do it all the time. Right?

Wrong.

I mean, you can.

But you can’t.

I mean, here’s what I mean.

The LOLWTFBBQ of estimating calorie (energy) output

Let’s start here: calculating daily energy output. In other words, finding out how many calories your body uses every day — your average daily metabolic rate.

Most people use calculators on the Internet to find their average daily metabolic rate. Google search ‘metabolic rate calculator’, and you’ll find hundreds of different calculators.

Some of them estimate your basal metabolic rate (BMR), which is the amount of energy you’d output if you did nothing but rest in bed all day. You do more than rest in bed, but let’s assume you didn’t.

Let’s assume you play Zelda in bed all day. Some caretaker comes around and wipes your ass after you shit your pants. Coffee in the morning will make that happen.

I found three different BMR calculators. I gave each website the same pieces of information (height, weight, age) and here’s what happened:

- active.com: 2,123 calories per day

- calculator.net: 1,998 calories per day

- bmrcalculator.org: 2000 calories per day

How can each calculator poop out a different result despite being fed the same information? Gah. Oh well. The variance between each result isn’t huge. I’m fine. Right?

Part dos of the LOLWTFBBQ of estimating calorie (energy) output

I have my BMR. Or what I believe to be my BMR. But, hey, I’m smarter than the average sasquatch. I know a bunch of things influence my daily metabolic rate. I know my daily metabolic rate isn’t my BMR unless I do nothing beyond soil myself as I set out to slay Ganondorf.

I want to get a more accurate estimate of my daily metabolic rate.

I know that my physical activity is a factor; if I move around more, I’ll use more energy. I know that my body composition is a factor; muscle is more metabolically active than fat, which means a 200 pound person with 10% body fat will have a higher metabolic rate than a 200 pound person with 30% body fat.

I don’t want to ignore these things, so I look for a total daily energy expenditure (TDEE) calculator. (I’m going to assume you aren’t sinking in a confusing sea of acronyms even though I realize the possibility.)

Google takes me to tdeecalculator.net. I punch in my activity level and body fat percentage. I’m told that my TDEE is a whopping 3,691 calories per day.

lolwut.

Not long ago, I was working with a 2000 calorie per day BMR. Now I’m being told I can house 3,691 calories per day. In other words, every day I can eat six more Snickers® bars than I originally thought I could.

TDEE, BMR, and LOL

Considering my BMR is the amount of calories I’d burn if I were decomposing in a nursing home, I’m going to use my TDEE estimation for calorie counting purposes. Because, hubris. And because, uhhh, I’m not dying. I mean, I am dying. We’re all dying, but…

End of story. See you later. I’m going to go buy some Snickers®.

/VOMIT

Couldn’t you see I was leading you down the wrong path on purpose to set up a plot twist? This is my signature move. Get used to it.

Here’s the deal…

Although many things do influence your metabolic rate, more often than not, accounting for every known variable gives you an illusion of control more than actual control.

BODY COMPOSITION

Your body composition does influence your metabolic rate. Muscle is more metabolically active than fat. But, chances are, the body fat percentage you think you have is wrong — a product of another flawed process.

Home body fat measurement tools like bioelectric impedance scales are stupid. They’re too sensitive to hydration. You can measure your body fat at 8:00AM, get a result, drink five glasses of water, measure your body fat at 8:05AM, and then get a totally different result. Body fat calipers also have big error in untrained hands.

In general, most ways to measure body fat in the comfort of your own home are bogus. They confuse rather than clarify. Unless you’re getting results via hydrostatic weighing, BodPod, or DEXA, the body fat percentage you think you have is wrong.

PHYSICAL ACTIVITY

Physical activity also influences your metabolic rate. But, often times, defining your physical activity is a crap shoot. For instance, the TDEE calculator mentioned above gives five different activity categories:

- Sedentary (office job)

- Light exercise (1-2 days/week)

- Moderate exercise (3-5 days/week)

- Heavy exercise (6-7 days/week)

- Athlete (2x/day)

But these categories don’t even define the type of exercise being done. Are you jogging? Sprinting? Strength training? And, to make matters worse, us humans suffer from all sorts of cognitive biases that make us overestimate just how active we really are.

Meaning I’m going to report (I did report) that I exercise vigorously, when, really, REALLY REALLY, I probably only exercise moderately.

The equations themselves

Even if you account for the errors in the input variables, there’s inherent error in the equations themselves. This is why three different calculators spit out three different BMR estimates.

The equations these calculators are built with are a product of averages. But there’s a chance you deviate from average.

For instance, losing weight tends to lower your metabolic rate. If you weigh 250 pounds and get down to 200 pounds at 15% body fat, you’ll likely have a lower metabolic rate than someone that’s 200 pound at 15% body fat “naturally.”

Part w/e of the LOLWTFBBQ of estimating calorie (energy) output

Let’s hop back to the TDEE calculation. I was estimated to have a TDEE of 3,691 calories. But, well, I was using estimates to get this estimate. If using estimates in order to estimate something sounds like a recipe for estimation error, that’s because it is.

I plugged in values for both body composition and physical activity, neither of which were 100% accurate. In other words, the likelihood of my TDEE being 3,691 calories isn’t great.

To make matters worse, things get hairier than an Italian man’s arms. For instance, non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT) also impacts your metabolic rate. NEAT is the energy you use when you’re macromoving, but not exercising.

Are you sitting upright, or are you slouching? (Sitting upright uses more energy.) Are you shivering right now? (Uses more energy.) Picking your nose? (Uses energy, unless you eat the booger.)

No metabolic rate calculator overtly accounts for NEAT. In other words, the likelihood of my TDEE being 3,691 calories is even less great than it was two paragraphs ago, before I mentioned hairy Italians and boogers.

Part finito of the LOLWTFBBQ of estimating calorie (energy) output

The only way to know your true metabolic rate is to lock yourself into a vacuum sealed room that’s able to measure all of the heat that escapes from your body.

You don’t have access to one of these rooms. Gaining access to one of these rooms is useless unless you also plan on abandoning your life and living inside for a few days.

I don’t know about you, but I’d rather spend my holiday time drinking hazy IPAs and eating Havarti cheese, numbing myself to the absurdity of the world, rather than being locked away in a vacuum sealed torture chamber in the name of metabolic enlightenment.

Point being: any quantification you have of your energy output — your daily metabolic rate — is a baby born from a soupy estimation orgy.

I’m going to press pause and shift focus. Before I get to the implications, I have to break down the flip side of counting calories: measuring energy intake.

The LOLWTFBBQ of estimating calorie (energy) intake

The classic way to measure energy intake is by counting calories. In other words, you find out how many calories are in standard measurement of the food, and then you measure how much of the food you eat.

You can find out how many calories a food contains via nutrition facts. The nutrition facts’ll say: one serving of this food contains so-and-so calories. (Click this link to visit a webpage by the FDA about nutrition labels if you’re unfamiliar with them.)

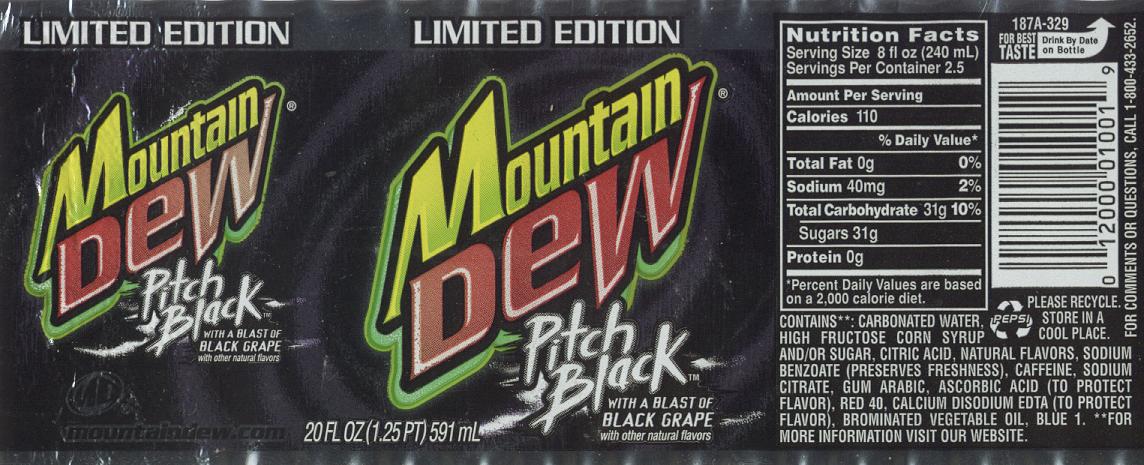

The “one serving” detail is important because one “package” isn’t always one “serving.” One bottle of Mountain Dew, for instance, is sometimes 2.5 servings. You have to read the fine print.

A lot of prepackaged foods have nutrition facts listed on the package itself, which makes it easier to track calorie intake. Fresh foods are (usually) trickier. Apples don’t have labels.

But Google is a powerful tool. You can find the nutrition facts for just about any food online. For instance, nutritionvalue.org tells me there are 58 calories in 100 grams of a Granny Smith apple. Problem solved.

The LOLWTFBBQ (again) of estimating calorie (energy) intake

Do you hear it coming?

The shit storm?

Unfortunately, calculating energy intake is just as flawed as calculating output. Because, uhhh, bacon.

Yes.

Bacon.

You find out there are 80 calories in two cooked strips of bacon. This is what the bacon package says. So you put two strips of bacon in a pan. You cook ’em up.

From experience, you know that grease yield is correlated to bacon crispiness. In other words, the longer you cook the bacon, the more grease cooks off.

How does this factor into the 80 calorie estimate? If you like under-cooked chewy rubbery bacon is there more calories in those two slices?

Good question.

I don’t know the answer.

The calories you eat aren’t the calories you absorb

Nutrition labels are vague by necessity. They are based on averages. Perhaps you ate 100 calories worth of bacon instead of 80 calories.

Seems trivial, but imagine if this margin of error replicated. For every 80 calories you thought you ate, you actually ate 100 calories. At the end of the day, you’d sleep thinking you ate 2000 calories when, really, you ate 2500 calories.

According to an article in The New York Times, food labels can be wrong by up to 25%. Not because of bacon blunders, but, rather, because the amount of calories you pour down your gullet isn’t necessarily the amount of calories your body absorbs.

Here’s an explanation. Or three.

ONE

Each macronutrient requires a different amount of energy to break down and digest. This is referred to as the thermic effect of food (TEF).

For instance, it takes more energy to break down proteins than it does fats. So eating 100 calories of fats yields more energy than eating 100 calories of proteins.

TWO

Cooking and processing make foods easier to absorb, which means we expend less energy in an attempt to digest them. Its like the difference between hammering down a brick wall and blowing over a tepee.

So if you eat a 100 calorie non-processed food, your body will spend more energy to digest it as compared a 100 calorie processed food. In other words, your body absorbs more of the processed food’s calories.

Or two.

Headlines get your attention

I could go on. There are more reasons why counting calories and measuring food intake is a crap shoot. Bottom line of all this being:

- We don’t really know our energy output, and estimating it is tough.

- We don’t really know our energy intake, and measuring it is tough.

In other words, despite energy balance and thermodynamics ruling the world of body composition, hacking the system is impossible.

But…

BUT…

I’m a piece of shit.

Piece of shit is me

I’m a piece of shit because I’m nitpicking. On purpose. Putting the appropriate spin on things because headlines are everything… or something. Pretending to be smarter than I really am.

Because, despite it being impossible to “hack the system,” the only way to navigate this alphabet soup is to… hack the system.

Calculating your energy output is flawed. Measuring energy intake is flawed. Counting calories as a strategy is imperfect. Very imperfect.

But you still need to do it.

Why you need to count calories

Counting calories is the only hand you have to play with the cards you’ve been dealt. You just have to understand one thing (that most people don’t): everything is a shitty imperfect estimate.

Too many people approach calorie counting as if they are holding the law in their hands, which turns things into one shitty game of cops and robbers. You do the work, you have the numbers in front of you, you go HAM, and things don’t work as expected.

What’s wrong? Why isn’t this working? I’m eating less than I’m burning. Why can’t I lose weight? Must be my genetics. I knew I wasn’t built for this.

But that’s not the case. You’re just getting duped by the world; you weren’t equipped with the proper expectations and mindset, which is that (a) everything is an estimate, and (b) we know less than we think we do.

The answer isn’t to get more specific and detailed in an attempt to gain control over the situation. That just screws things up. The answer is to zoom out. To go broad. To not be as anal with calorie counting (because there is error all over the place anyways). To embrace trial and error. To use real feedback to guide the process.

The first, sexier

You might now be wondering… How? How do you take the last paragraph and put it into practice? I’ll get to this sooner or later. I want to stay focused and connect with something I mentioned earlier.

I said there were two reasons why all of this energy balance talk is shit. Above is the second reason. Thermodynamics (and energy balance) is true, but hacking its source code isn’t as easy as it appears. A lot of people get duped by the numbers because they associate them with certainty. But there is none, initially.

Now its time for the first reason. The sexier reason. The reason why the people that say “I want to lose weight” are doomed.

→ Click here to read Part 3: Why counting calories is a game for idiots that are… idiotic. Pretend this sentence is a yo mamma joke, I’m out to offend.