Z2B

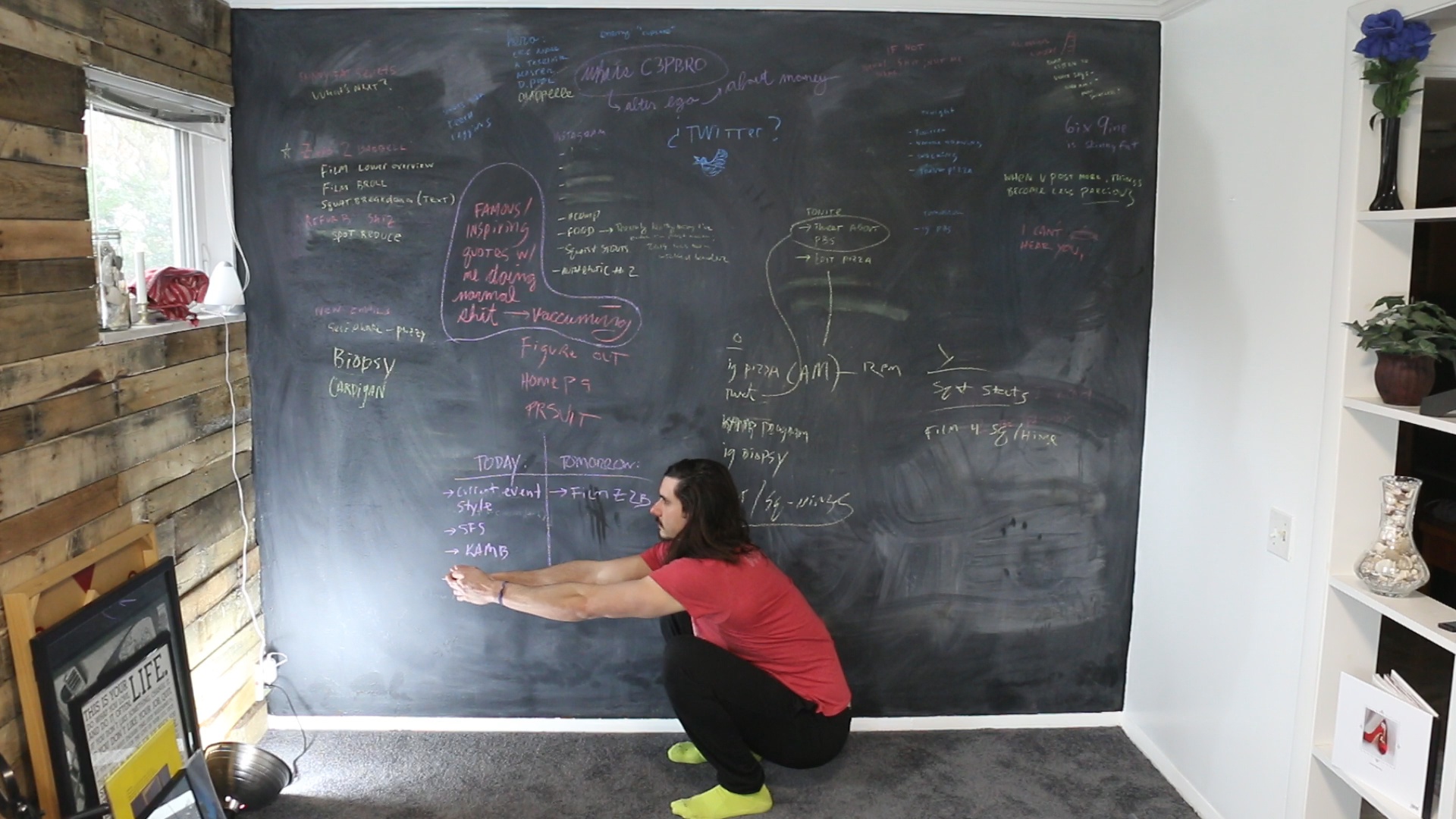

This is the squat section of Zero to Barbell: an aptitude test for identifying the weak, stiff, and tight areas of your body that increase your odds of injury and prevent you from doing basic barbell exercises with efficient technique.

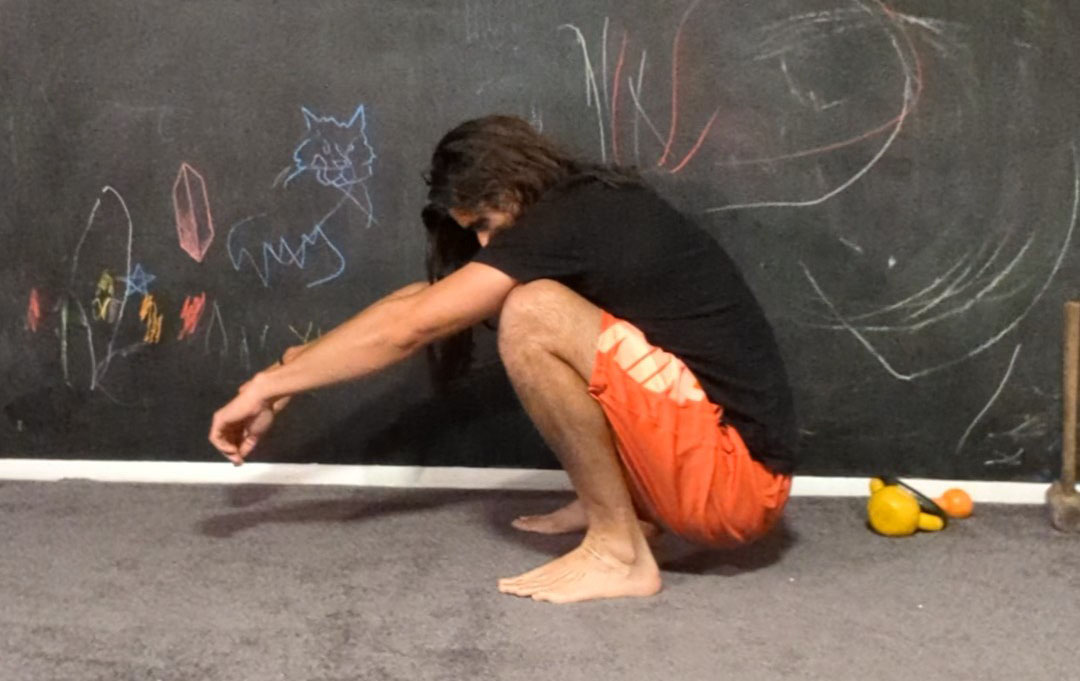

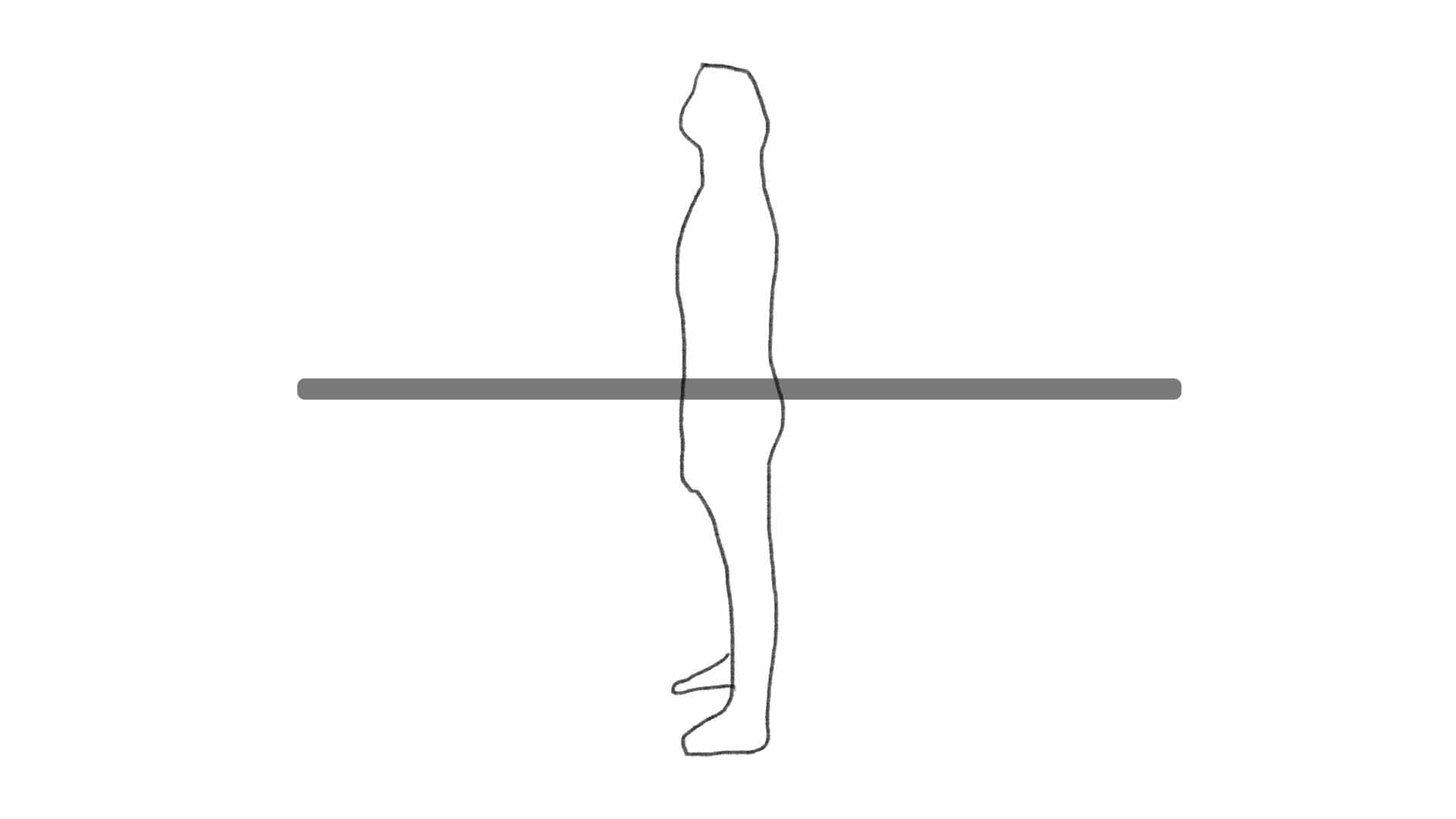

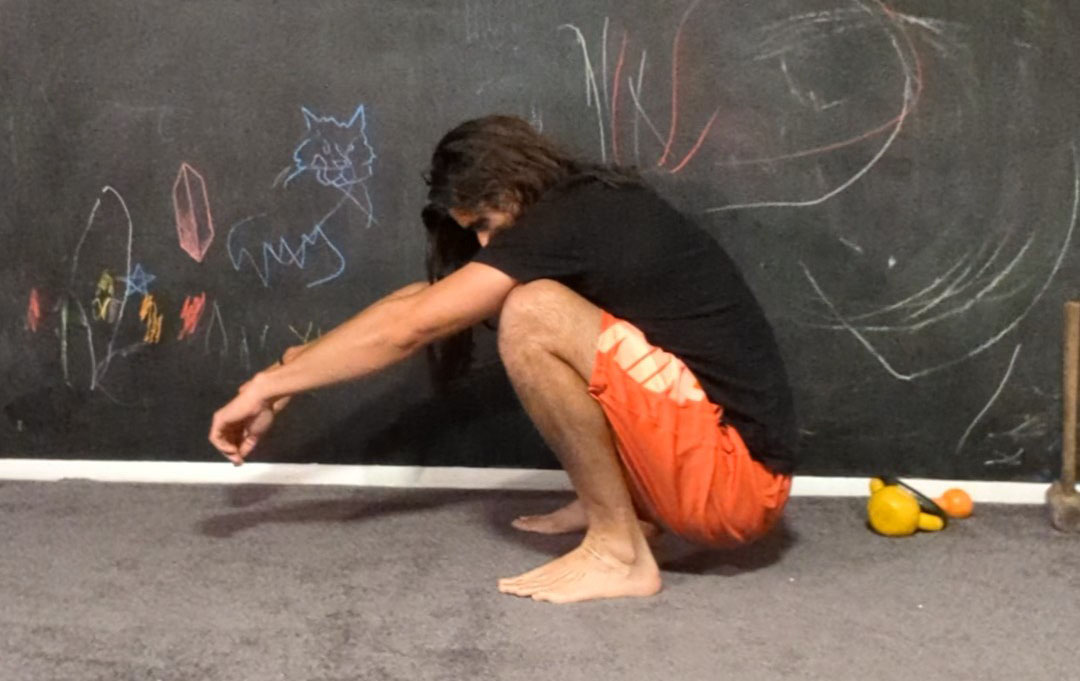

Squatting is all about vertical hip movement from a standing position. You can diagnose your general readiness for squatting with the square squat.

Stand with your feet below your hip sockets. Toes point forward. Drop your hips drop toward the floor. Descend until your hamstrings fully cover the calves. Return to the starting position. (Try to keep your spine in a neutral position throughout the square squat, especially at the bottom of the squat.)

Common problems: unable to squat to full depth (hamstrings over calves), arches of the feet collapse, feet rotate outward near the bottom of the squat (easy to see when performing the square squat in socks on a more slippy surface), can’t keep the heels glued to the floor throughout the exercise…

If you can’t perform a proper square squat and are encountering one or more of the problems above, the following battery of tests will reveal your limiting factors.

1. Test ankle-flexion flexibility with wall squats.

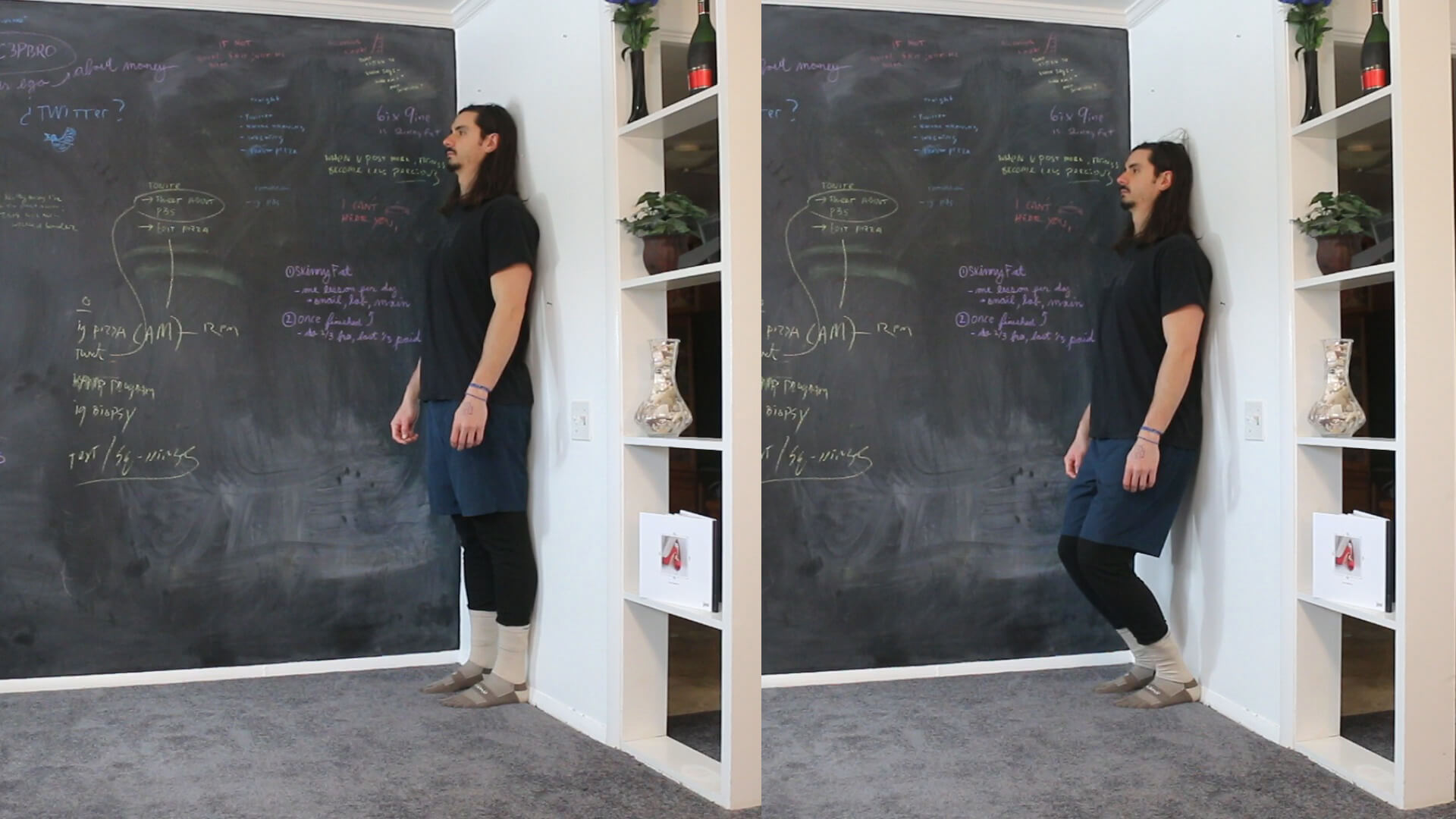

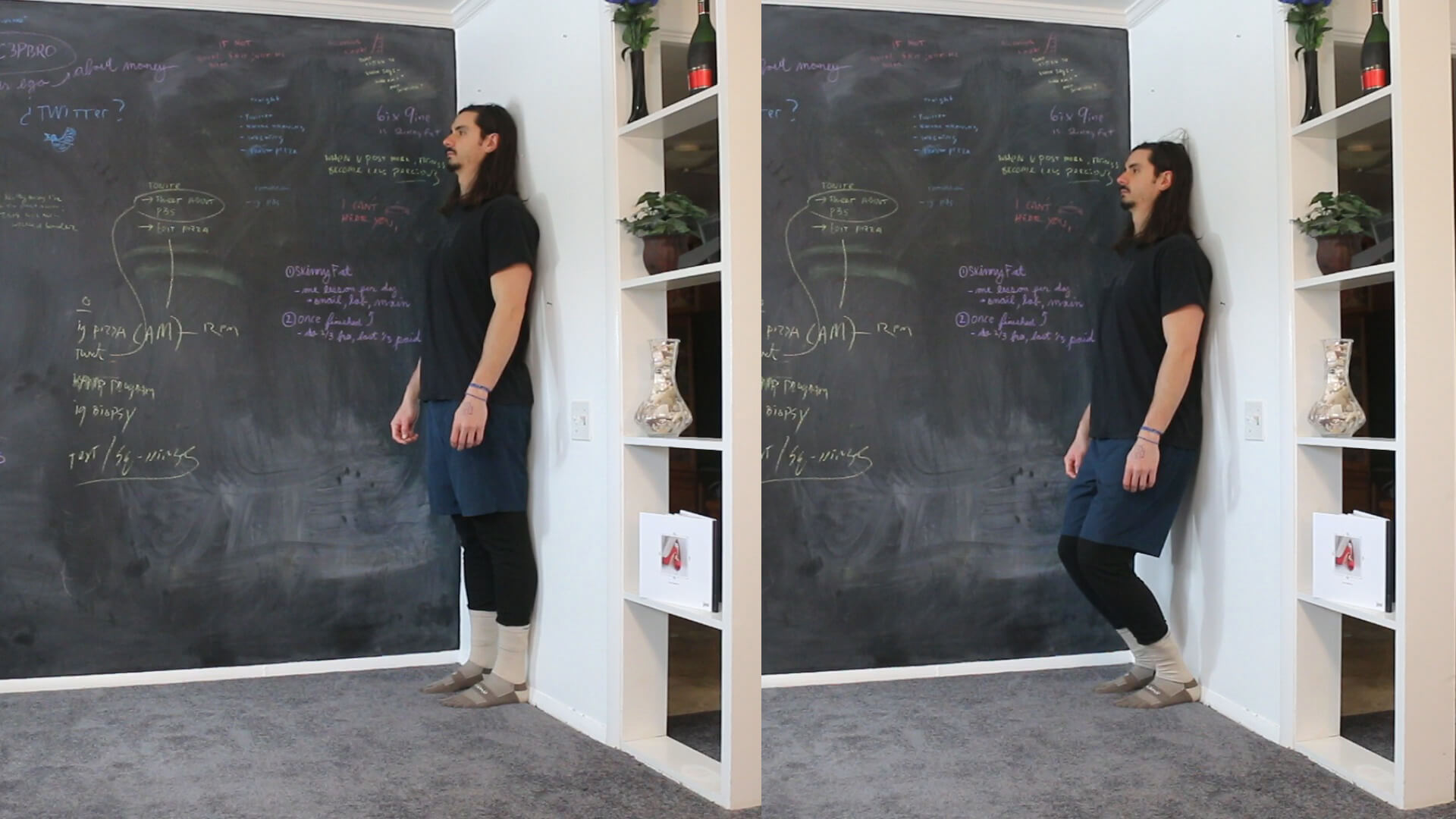

Stand with your backside against a wall. Feet under hip sockets. Toes face forward. Heels, butt, upper back, and head glued to the wall. Distribute your weight across your tripod and your toes.

Bend your knees and slide your hips down the wall toward the floor. Descend as far as you can while maintaining form: hips, upper back, and head glued to the wall; knees tracking over toes. At your deepest depth, how far are your knees over your toes?

If your knees can’t travel at least a few inches past your toes, you’ll struggle with square squats because you lack ankle-flexion flexibility.

Ankle-flexion flexibility is the ability to passively compress the top of the foot into the front of the shin.

During a squat, ankle-flexion flexibility is what allows your knees to travel over your toes (assuming your tripod stays intact). Without this, you’ll probably rise onto your tip toes as you descend deep into the squat instead of staying flat-footed.

MORE

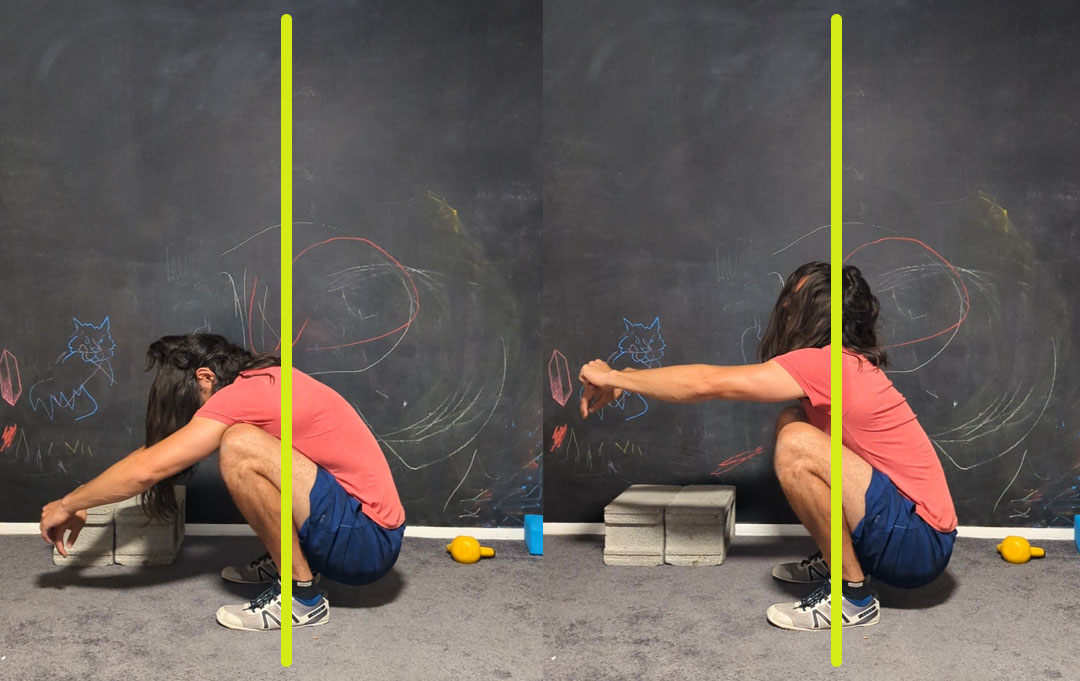

Wall squats are pure squats. Remember, squatting is defined by vertical hip translation. The wall prevents horizontal hip translation, and the hips travel in a 100% vertical line.

Without horizontal hip translation, the only way to drop the hips is by pushing the knees over the toes. Assuming the tripod stays intact, this is a function of ankle-flexion flexibility and only ankle-flexion flexibility.

The relationship is rather straightforward: more ankle-flexion flexibility allows the knees to travel further over the toes which unlocks deeper wall-squat depth.

Once you max out ankle-flexion flexibility, there’s only one way for the hips to drop deeper: abandon the tripod and balance on your tippy toes. (Only those with superhuman circus-like ankle-flexion flexibility can do a full-range wall squat with the tripod intact.)

There’s nothing inherently wrong with tippy-toe squats. Contrary to popular belief, tippy-toe squats aren’t dangerous. You should be able to do tippy-toe squats without pain.

Unfortunately, rising onto your tippy toes to reach proper squat depth isn’t an ideal tradeoff during barbell squats because balance becomes a bottleneck. You’re more stable (and can transmit force better) when your entire foot is anchored to the floor. Stability and better force transfer are good when you’re trying to lift as much weight as you possibly can (which is often the goal during barbell squats).

Even though square squats don’t restrict the hips, the relationship between ankle-flexion flexibility and depth remains: greater ankle-flexion flexibility unlocks more square-squat depth; lesser ankle-flexion flexibility restricts square-squat depth. And, more often than not, the same wall-squat compensation will happen during square squats: When ankle-flexion flexibility maxes out and you’re still trying to reach a deeper squat depth, your heels will pop off the floor and your weight will shift toward your toes.

SUM

Perform a wall squat.

If you can get your knees a few inches past your toes while maintaining your tripod, you probably have enough ankle-flexion flexibility (for now).

If you can’t get your knees a few inches past your toes, you lack ankle-flexion flexibility and you will struggle with squats of all sorts.

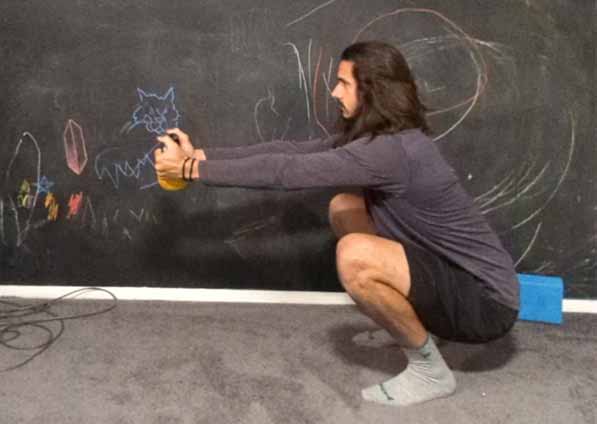

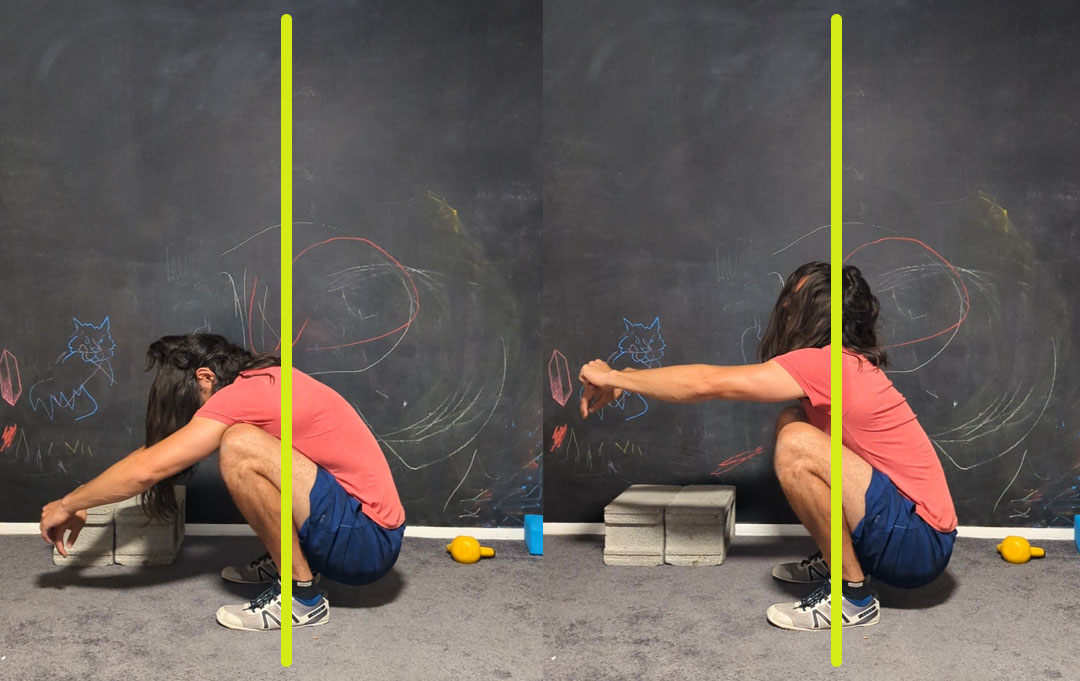

2. Test ankle-flexion mobility with weighted arms-out square squats.

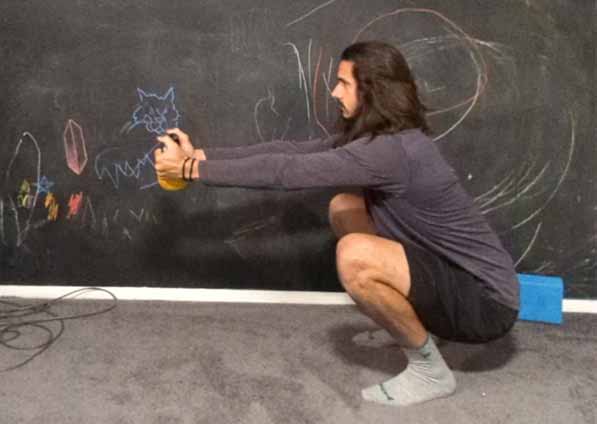

Grab a 10 or 20-pound weight. Hold it in front of your body with your arms extended. Perform a square squat: feet below your hip sockets; toes forward; hips drop toward the floor until your hamstrings fully cover the calves. (Try to keep your spine in a neutral position.)

If you CAN do weighted arms-out square without problems, but can’t do unweighted (normal) square squats, you might lack ankle-flexion mobility.

Ankle-flexion mobility is the ability to actively pull the top of the foot into the front of the shin.

During a squat, ankle-flexion mobility maintains the ankle angle and counterbalances the mass of the hips and torso in the bottom position. Without this, you’ll probably fall onto your butt (or back) if you try descending into a deep squat position. Chances are, your body is smart enough to stop this from happening and, instead, you won’t be able to achieve a full range of motion. Your hips will be high and your torso will drop forward, with your arms extended in front of your body.

MORE

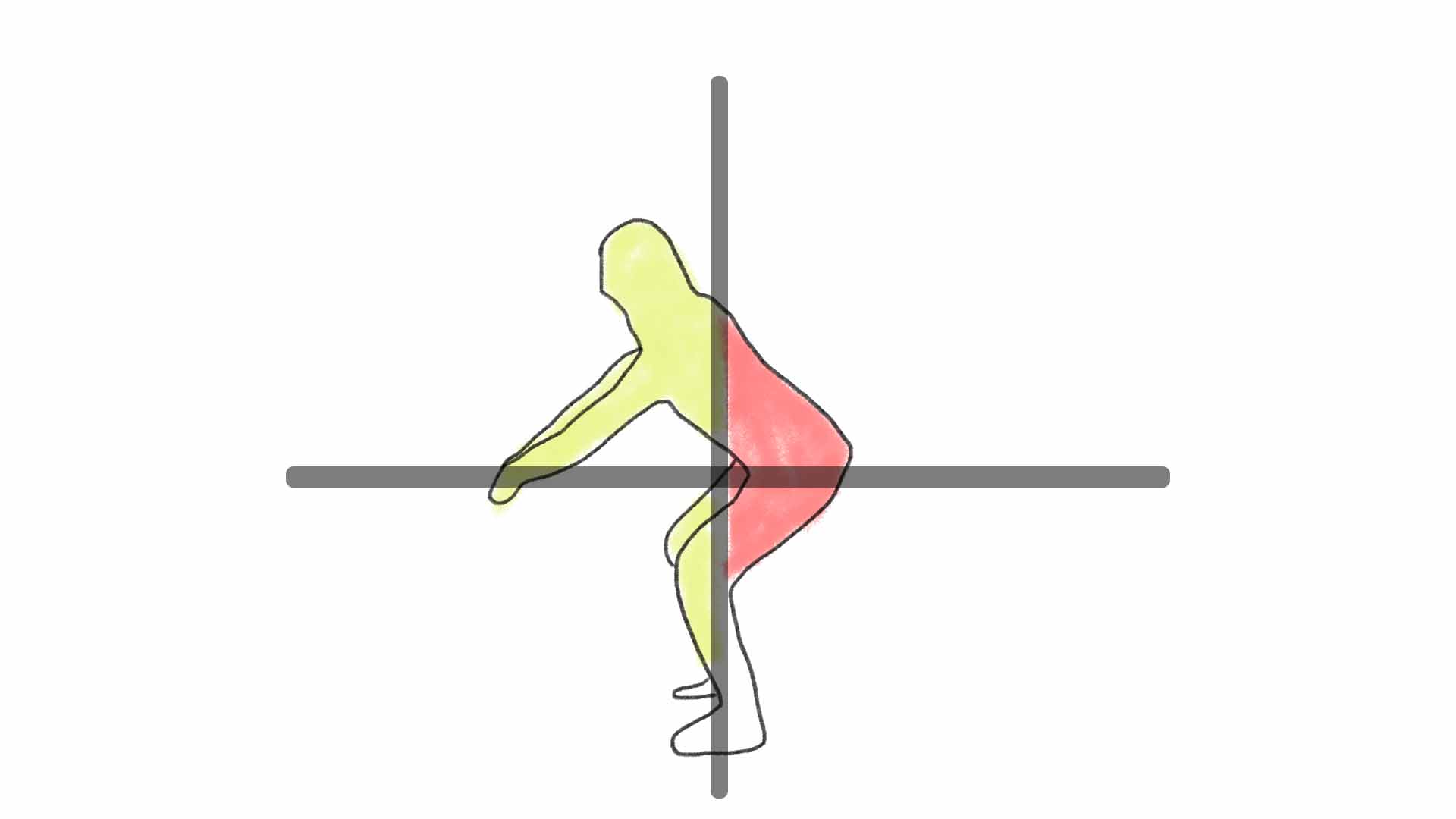

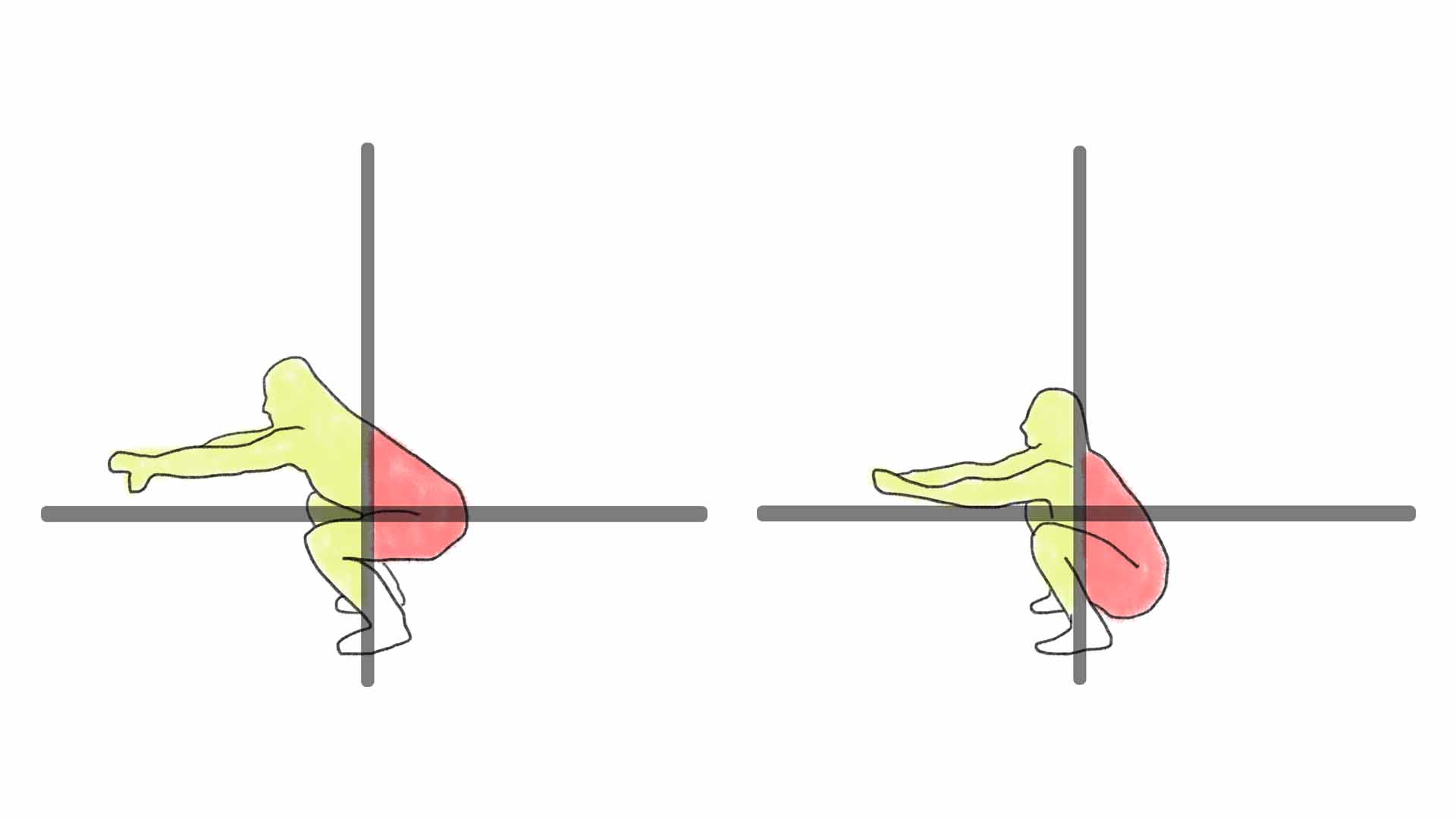

Your body is a seesaw during square squats. When you’re standing upright, before you begin the squat, you have a balanced seesaw.

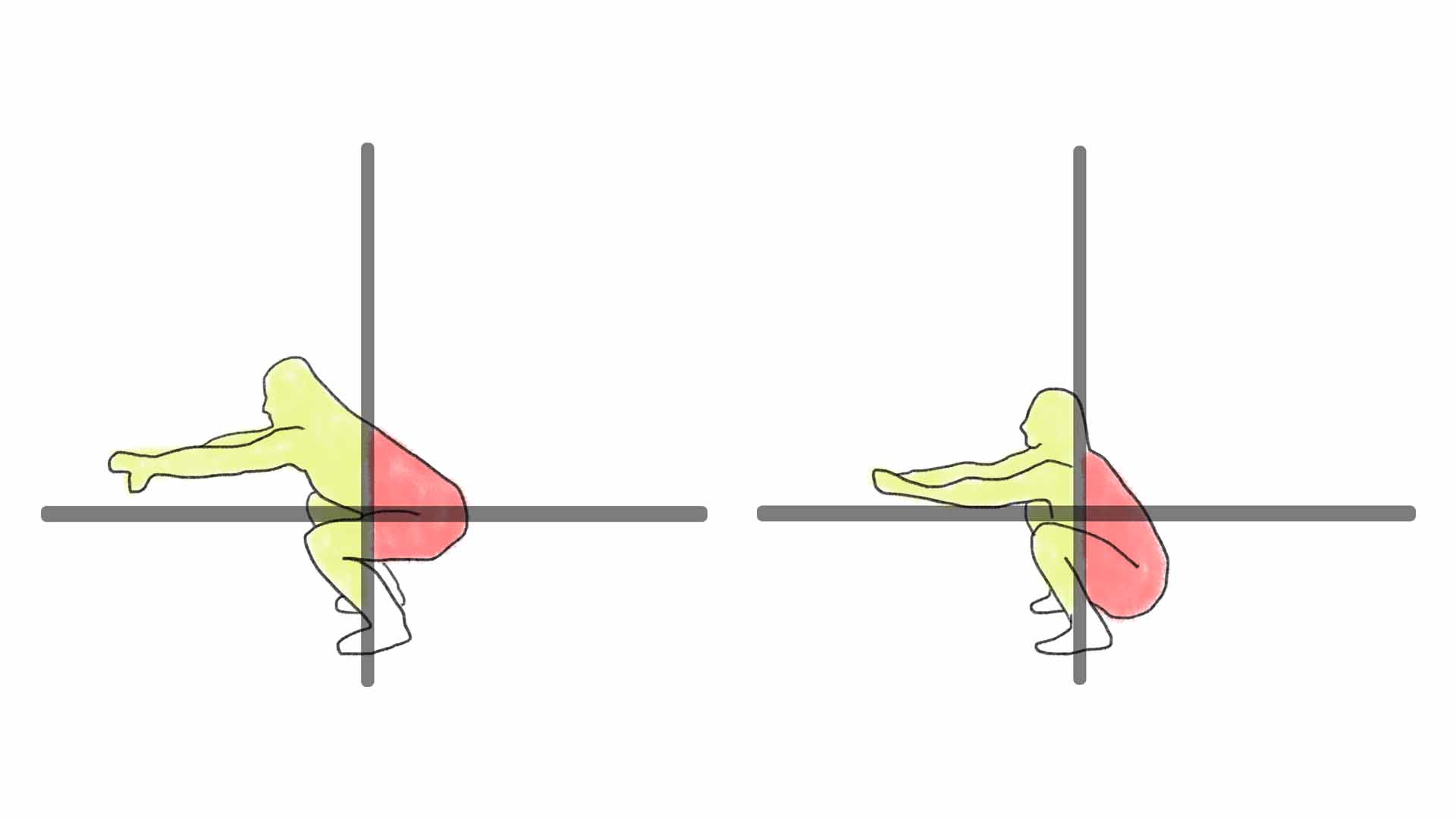

When you descend, two things happen (somewhat simultaneously). First, the knees punch forward. This kicks some mass toward the front of the seesaw. Second, the hips drop down and back. This throws a lot of mass toward the back of the seesaw.

Chances are, you will naturally offset the mass of the hips going backward by dropping your torso and reaching your hands forward. Your body intuitively keeps the system in balance (or tries to).

Unfortunately, things get a little screwy as the squat continues. For unavoidable biomechanical reasons, when the hips drop below parallel, the torso adopts a more vertical position, which throws most of the mass toward the back end of the seesaw.

When this happens, the mass on the front side is outmanned. You have to exert muscular force to keep the seesaw in balance, and your shin muscles shoulder most of the burden. They have to contract to maintain the angle of the ankle, which keeps the knees over the toes. This is a function of ankle-flexion mobility.

With poor ankle-flexion mobility, once you go below parallel, the weight on the back side of the seesaw will pry your ankle apart, and you’ll fall on your butt (or your back). Your body will circumvent this (because it doesn’t want to fall backward) by preventing you from dropping your hips below parallel. Your torso and upper body will reach forward, to add mass to the front of the seesaw.

Holding a weight at arm’s length adds mass to the front end of the seesaw, which reduces the demand on your shin to exert force. This makes it easier to perform a full-range square squat in the presence of poor ankle-flexion mobility. Also, note how ankle-flexion flexibility impacts the system: Greater ankle-flexion flexibility allows you to get your knees further over your toes, which adds weight to the front of the seesaw.

SUM

Perform a weighted arms-out square squat.

If you can perform a weighted arms-out square squat, yet you struggle with “normal” square squats, you might lack ankle-flexion mobility.

If you can’t perform a weighted arms-out square squat, you probably lack ankle-flexion flexibility. (You can confirm this by evaluating your performance on the wall squat.)

Third, test hip-flexion flexibility with passive knee pulls.

Lie on your back and pull your knee to your chest with your hands. Be strict with your spine: Keep your lower back in a neutral position. Also, make sure you pull your knee back straight from its socket, toward your midline (nose). Don’t pull your knee sideways away from your midline, toward your shoulder.

You should be able to squash a good deal of your thigh into your torso without any discomfort or pinching pain in the front of your hip. If you don’t have at least 135 degrees of hip-flexion flexibility, or if you experience discomfort in the hip capsule during this stretch, you’ll struggle with square squats because you lack hip-flexion flexibility.

Hip-flexion flexibility is the ability to passively compress the thigh into the abdomen.

During a square squat, the hips flex. And the degree of hip flexion required is correlated to squat depth. The further you descend, the more your hips flex.

This relationship isn’t super straightforward though because your body can work around subpar passive hip flexion by rounding the lower spine.

The angle of hip flexion is set by the position of the spine. When your lower spine rounds, you aren’t in as much hip flexion.

Return to the stretch above. (Lie on your back and pull your knee to your chest keeping a neutral spine.) This time around, when you reach your maximum range of motion, round your lower back. You’ll probably be able to pull your knee tighter to your stomach.

Same thing happens during the square squat. When you run out of passive hip flexion from a neutral-spine position, your lower back will round, allowing you to pancake your thigh further into your stomach, unlocking a deeper depth. From a square-squat standpoint, this isn’t a big deal, but it might cause some problems during barbell squats.

SUM

Perform a passive knee pull.

If you can’t pull your knee to create at least x angle, or if you experience any tightness or discomfort in the hip capsule during, you might lack hip-flexion

Fourth, test hip-flexion mobility with active knee pulls.

Lie on your back and pull your knee to your chest without using your arms. Be strict with your spine: Keep your lower back in a neutral position. Also, make sure you pull your knee back straight from its socket, toward your midline (nose). Don’t pull your knee sideways away from your midline, toward your shoulder.

If you don’t have at least 135 degrees of hip-flexion mobility, or if you experience discomfort in the hip capsule during this stretch, you’ll struggle with square squats because you lack hip-flexion mobility.

If you don’t have at least 135 degrees of hip-flexion mobility, or if you experience discomfort in the hip capsule during this stretch, you’ll struggle with square squats because you lack hip-flexion mobility.

Hip flexion mobility is…

compressing the knee and the thigh into the abdomen and the chest.

Why?

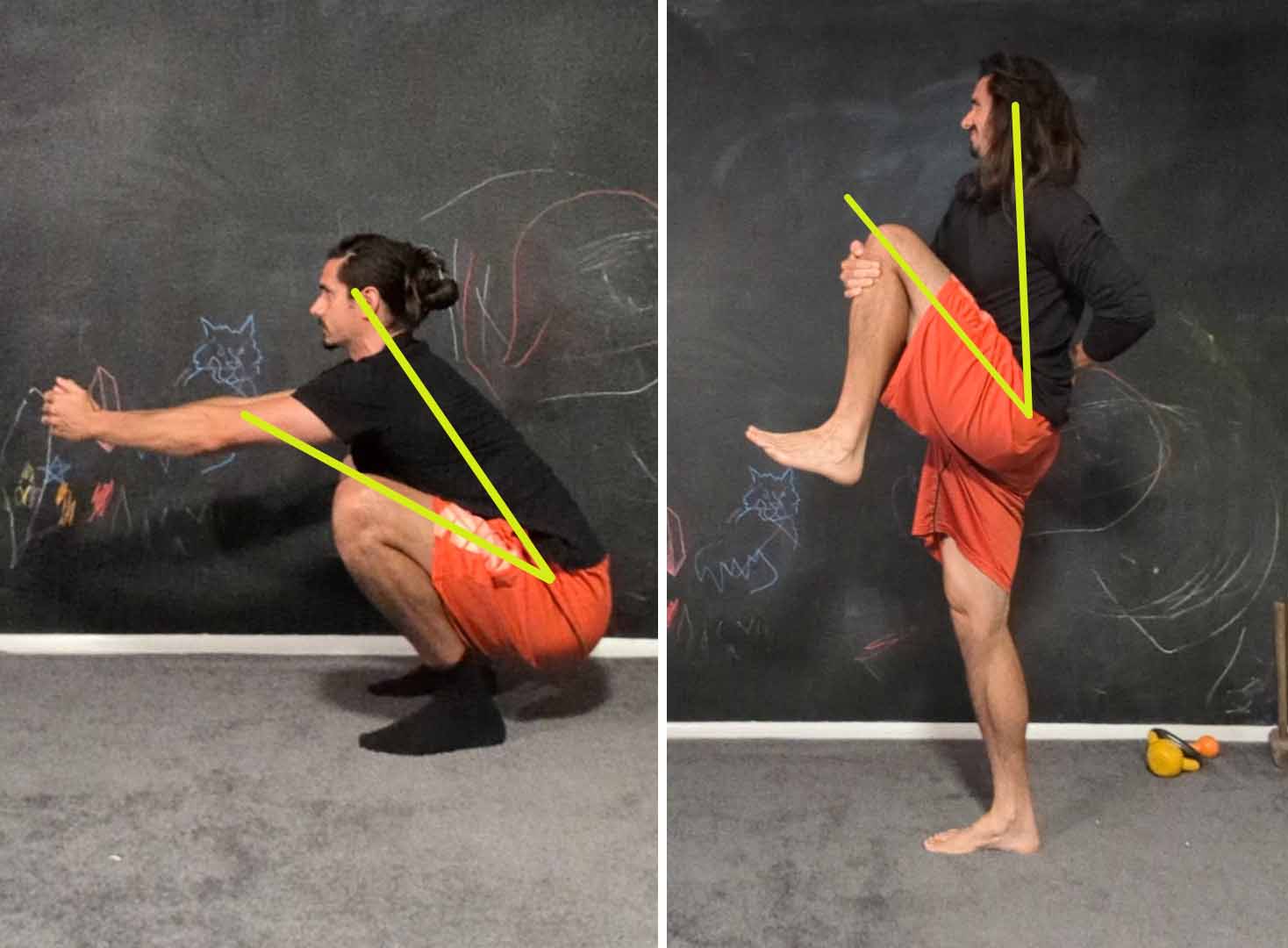

Hip flexion is often seen as a passive aspect of squatting: Your hips get squashed into your torso because of gravity. This is true during the beginning of the squat, but as you sink deeper, the line of compression changes. In order for an external force to really bully your hips into maximum hip flexion, the compression needs to be at a 30 or 45-degree angle.

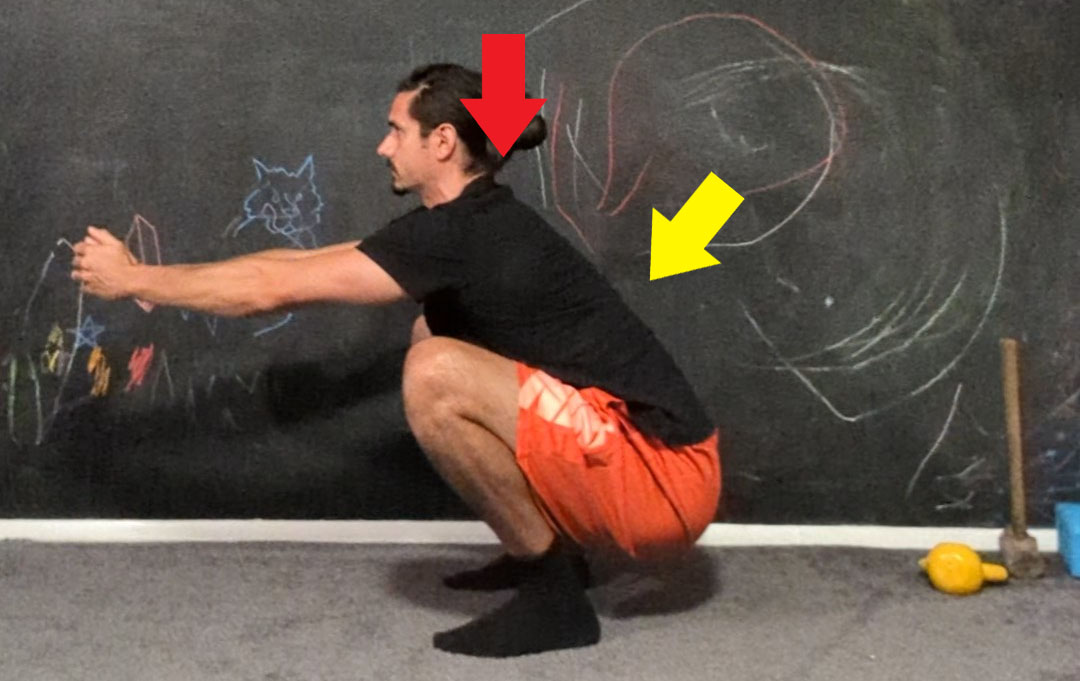

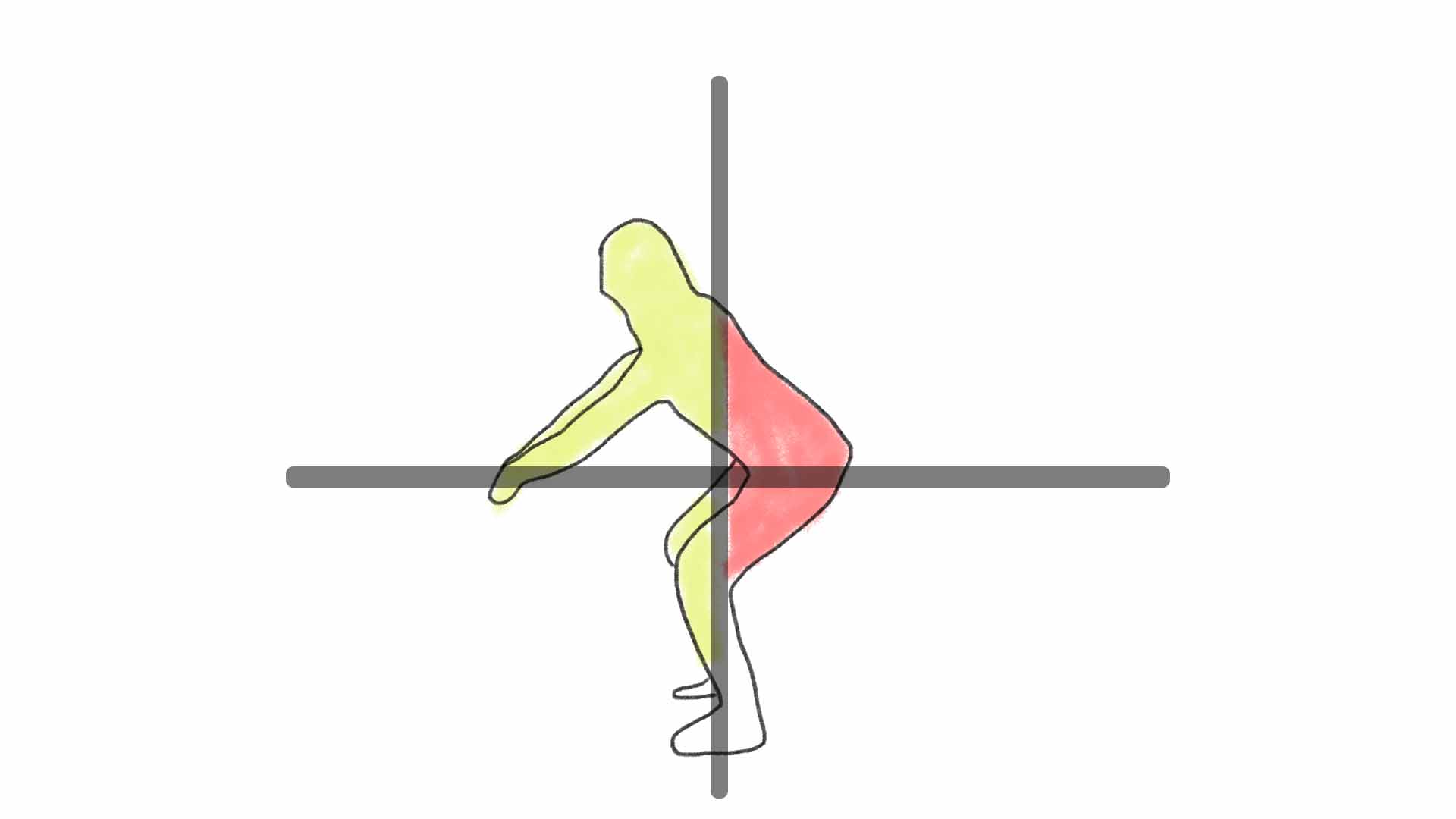

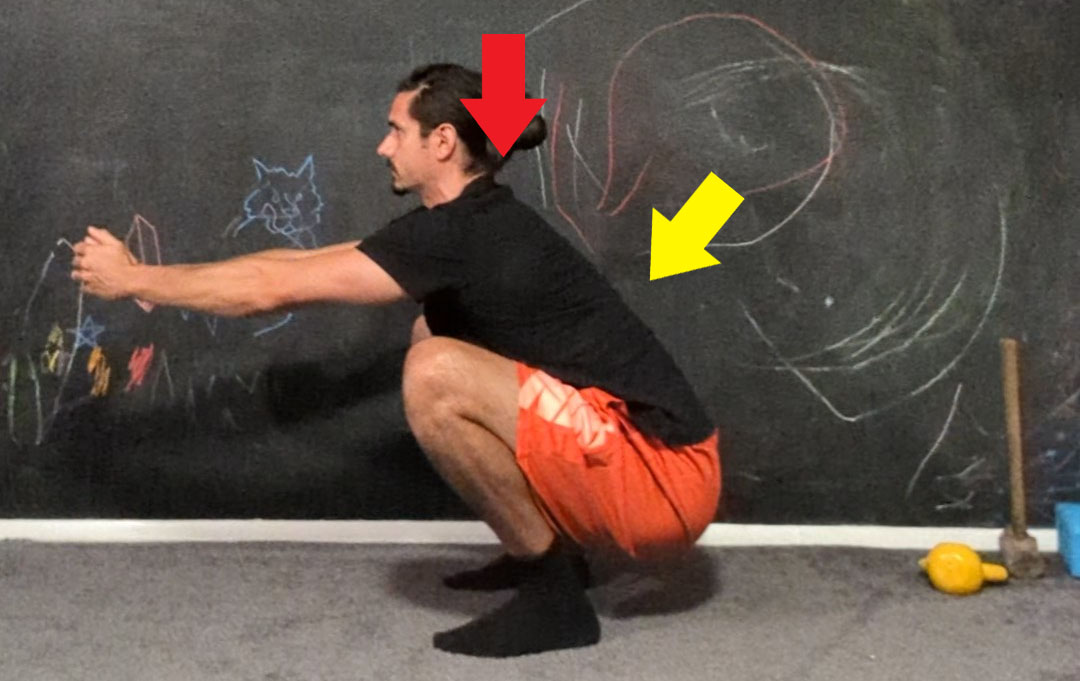

The red arrow represents gravity’s downward compression. The yellow arrow represents the optimal angle for compressing the thighs into the torso.

And so, there is some compression, but not maximal possible compression. This is important because flexibility can only be unlocked passively. In other words, if you’re relying on passive hip flexion, your hips will only compress as far as they are forced into position. And with the downward force being off-angle, you may not unlock max hip-flexion flexibility.

more often than not, you’ll only be able to squat to depth of hip flexion mob w/ neutral spine. and attempts to go even deeper result in infamous buttwink or rounding.

If your mobility is on par with your flexibility, you will have an easier/comfier to sink deeper into the squat. b/c likely able to squeeze into tightest position and,

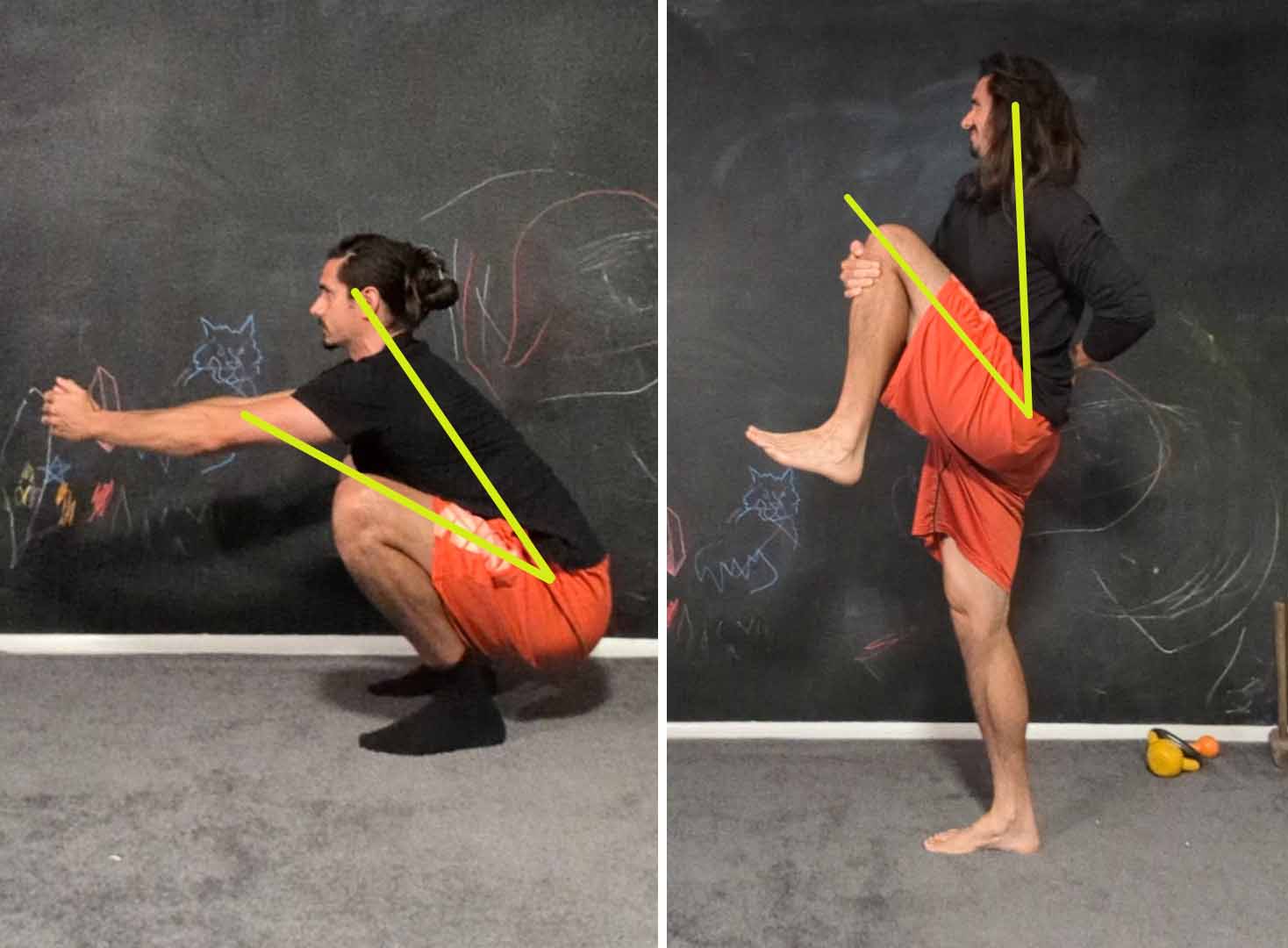

you’re below parallel, greater hip flexion brings the butt forward. From a seesaw standpoint, this means the mass on the back end comes closer to the fulcrum, which reduces torque. Less torque means the front end doesn’t have to work as hard to keep the seesaw in balance. (Think of how much effort it takes to hold a pair of dumbbells at arm’s length as compared to hugging them close to your chest.) Because of this, it may be easier to keep your torso upright in a rock-bottom squat.

Forcing an upright torso shifts more weight towards the back end of the seesaw, which means the front end has to work harder to keep balance. (Remember, this burden falls primarily on active ankle flexion.) With your hips closer toward the fulcrum, the front end will have an easier time keeping the system in balance.

ANKLE-FLEXION FLEXIBILITY

Passively compressing the foot into the shin so the knees travel past the toes. Major symptom of lack: can’t keep feet glued to the ground at a deep depth.

TEST

Stand with your backside against a wall. Feet under hip sockets. Toes facing forward. Glue your heels, your butt, your upper back, and your head to the wall. Keep your weight distributed across your tripod and your toes.

Slide your hips down the wall, towards the floor. Descend as far as possible, keeping your hips and your upper back glued to the wall and your heels glued to the ground. Stop when you feel your weight shift onto your toes, right before your heels pop off the floor. (Also, stop if your arch collapses.) How far are your knees over your toes?

Your knees should be able to travel a few inches past your toes. At least. If they can’t, you’ll probably struggle with square squats.

Why?

There’s a strong relationship between squatting deep and passive ankle flexion. Return to the test above, only this time don’t stop when your heels pop off the floor. Keep going until you reach proper square-squat depth (hamstrings cover lower legs).

Squatting against a wall like this yields a more “pure” squat. Remember, squatting is all about vertical hip translation. The wall prevents horizontal hip translation, keeping the hips in a 100% vertical path. Unfortunately, in order to maintain this 100% vertical path, the heels can’t stay glued to the ground. They’ll pop off the floor at some point (unless you have insane ankle-flexion flexibility).

This isn’t a bad thing. Tippy-toe squats aren’t inherently dangerous. You don’t see many people doing tippy-toe barbell squats because balance becomes the bottleneck.

You’re more stable (and can transmit force better) when your entire foot is anchored to the floor. Stability is good when you’re trying to lift as much weight as you possibly can. We veer away from “pure” squats as a tradeoff, to be able to lift more weights.

When doing a “pure” squat against a wall, your heels will pop off the floor when you run out of passive ankle flexion. In order words, if you keep your heels glued to the ground, the depth you’d achieve would be determined strictly by your ankle-flexion flexibility.

Even though square squats don’t confine the hips like squats against a wall, the relationship between passive ankle flexion and depth remains. Better ankle-flexion flexibility will unlock more square-squat depth. Worse ankle-flexion flexibility will limit square-squat depth.

ANKLE-FLEXION MOBILITY

Actively pulling the top of the foot into the front of the shin and strength in a knees-over-toes position. Major symptom of lack: at the deepest reachable depth, the hips are high and the torso is low (horizontal).

TEST

Do a square squat while holding a 10 or 20-pound weight in front of your body with your arms extended. Does this make the square squat easier? Can you suddenly do a square squat to proper depth?

Also, while in the bottom position, bring the weight closer to your body. What happens? Can you stay upright? Or do you fall backward?

If you CAN do a square squat with a weight at arm’s length, but CAN’T do one without weight or CAN’T do one with the weight closer to your body, you could probably use more active ankle-flexion strength. (If you can’t do a square squat with a weight at arm’s length, then you probably don’t have enough passive ankle flexion, let alone active ankle-flexion mobility.)

Why?

Square squats are like a seesaw. When you’re standing upright, you have a balanced seesaw. When you descend, a few things happen. First, the knees punch forward. This kicks some mass toward the front of the seesaw, but not much. Maintaining balance is easy. Second, the hips drop down and back. (This usually happens somewhat in tandem with the knees punching forward.)

When the hips drop down and back, a bunch of mass gets thrown on the backend of the seesaw. The other side has to compensate to maintain balance.

Chances are, your body will compensate naturally by reaching your hands forward. Your body intuitively keeps the system in balance (or tries to). The further forward your hands are the more torque they’ll produce, meaning the “heavier” they become.

Unfortunately, things get a little screwy as the exercise progresses. For unavoidable biomechanical reasons, when your hips drop below parallel, your torso adopts a more vertical position, which throws most of your mass on the back end of the seesaw.

When this happens, the mass on the front side is outmanned. You have to exert muscular force to keep the seesaw in balance, and your shin muscles shoulder most of the burden. They have to exert enough force to counteract the back-side weight.

With poor ankle-flexion mobility, the weight on the back side of the seesaw will pry your ankle apart, and you’ll fall on your butt (or your back). Holding a weight at arm’s length adds mass to the front end of the seesaw, reducing the demand on your shin to exert force. This makes it easier to square squat with poor ankle-flexion mobility.

When you bring the weight (or your arms) closer to your body, you’ll notice how much harder your shins have to work to keep you upright. Bringing the weight closer to the midline reduces torque, which screws with the seesaw.

(Also useful to note how ankle-flexion flexibility impacts the system: If you can get your knees far over your toes, you’ll have more weight on the front side of the seesaw.)

HIP-FLEXION FLEXIBILITY

Passively compressing the knee and the thigh into the abdomen and the chest. Major symptom of lack: spinal rounding during deep squats, needing to reach far forward at a deep depth.

TEST

Lie on your back and pull your knee to your chest with your hands. Be strict with your spine: Keep your lower back in a neutral position.

You should be able to squash a good deal of your thigh into your torso without any discomfort or pinching pain in the front of your hip. If you don’t have much hip-flexion flexibility or you experience discomfort in the hip capsule during this stretch, your square squat will suffer.

Why?

Hip flexion is an integral (yet often forgotten) component of squatting. During a square squat, the relationship between depth and hip flexion is straightforward: The deeper you descend, the more hip flexion you need.

This relationship isn’t super straightforward though because your body can work around subpar passive hip flexion by rounding the lower spine. Return to the stretch above. (Lie on your back and pull your knee to your chest keeping a neutral spine.) This time around, when you reach your maximum range of motion, round your lower back. You’ll probably be able to pull your knee tighter to your stomach.

Same thing happens during the square squat. When you run out of passive hip flexion from a neutral-spine position, your lower back will round, allowing you to pancake your thigh further into your stomach, unlocking a deeper depth. From a square-squat standpoint, this isn’t a big deal, but it might cause some problems during barbell squats.

HIP-FLEXION MOBILITY

Actively compressing the knee and the thigh into the abdomen and the chest. Major symptom of lack: spinal rounding during deep squats, needing to reach far forward at a deep depth.

TEST

Lie on your back and pull your knee to your chest without using your arms. Be strict with your spine: Keep your lower back in a neutral position.

Your active hip flexion should be close to your passive hip flexion. A huge gap between the two can affect how comfortably you can square squat.

Why?

Hip flexion is often seen as a passive aspect of squatting: Your hips get squashed into your torso because of gravity. This is true during the beginning of the squat, but as you sink deeper, the line of compression changes. In order for an external force to really bully your hips into maximum hip flexion, the compression needs to be at a 30 or 45-degree angle.

The red arrow represents gravity’s downward compression. The yellow arrow represents the optimal angle for compressing the thighs into the torso.

And so, there is some compression, but not maximal possible compression. This is important because flexibility can only be unlocked passively. In other words, if you’re relying on passive hip flexion, your hips will only compress as far as they are forced into position. And with the downward force being off-angle, you may not unlock max hip-flexion flexibility.

If your mobility is on par with your flexibility, you might be able to sink deeper into the squat. Even tiny improvements in your hip-flexion range of motion can have a massive effect on the squat. When you’re below parallel, greater hip flexion brings the butt forward. From a seesaw standpoint, this means the mass on the back end comes closer to the fulcrum, which reduces torque. Less torque means the front end doesn’t have to work as hard to keep the seesaw in balance. (Think of how much effort it takes to hold a pair of dumbbells at arm’s length as compared to hugging them close to your chest.) Because of this, it may be easier to keep your torso upright in a rock-bottom squat.

Forcing an upright torso shifts more weight towards the back end of the seesaw, which means the front end has to work harder to keep balance. (Remember, this burden falls primarily on active ankle flexion.) With your hips closer toward the fulcrum, the front end will have an easier time keeping the system in balance.

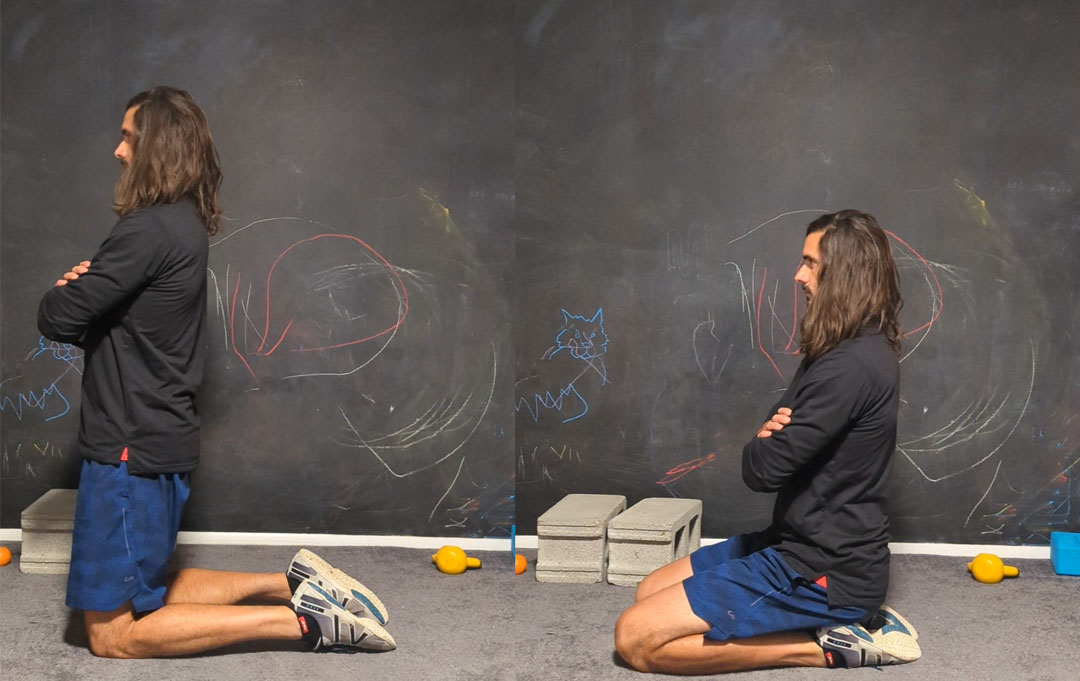

KNEE-FLEXION FLEXIBILITY

Passively bending at the knee to bring the heel to the butt. Major symptom of lack: knee pain during deep squats.

TEST

While “standing” on your knees, place your knees below your hips. Sit back on top of your legs.

You should be able to comfortably sit on top of your legs with no excessive pressure in or around your knees. If you’re unable to do this or you feel any sort of discomfort or pain, then this might carry over to square squats.

Why?

Too obvious for me to explain.

KNEE-EXTENSION MOBILITY

Actively bending at the knee to move the heel away from the butt. Major symptom of lack: knee pain during deep squats.

TEST

While “standing” on your knees, place your knees below your hips. Sit back on top of your legs. Return to the start position by pushing your feet into the ground and keeping an upright torso.

If you experience any pain in or around the knee during this, or if you have to drop your torso forward during this, then this might carry over to square squats.

Why?

Too obvious for me to explain.

WHAT NOW?

If you can’t do a square squat, I have good news. Few people do barbell squats with square-squat technique. In fact, I’d bet most people that do barbell squats can’t do square squats. (This isn’t a good thing, just an observation.)

The purpose of performing (or trying to perform) the square squat is to make it easier to diagnose deficiencies and limiting factors. (Remember, this is a flashlight, not a final answer. Everyone has different proportions. Figuring out your “problems” will require some experimentation and an open mind.)

Before you go crazy trying to rebuild your body, you should see if you can squat with a more barbell-friendly technique. First, widen your stance. Instead of hip-width, go shoulder-width. Second, point your toes out. Instead of pointing them forward, rotate them outward 10 to 30 degrees (whatever is most comfortable in that range). Third, squat down.

Ideally, with these two changes, you’ll be able to descend until the back of your thighs (hamstrings) sit on the back of your lower legs (calves). This is known as “ass-to-grass” (ATG) depth, which gets its name from squatting so deep your ass touches the grass (even though it probably won’t actually touch the grass).

These two changes make the squat easier because you’re able to squat between your legs instead of on top of them, and squatting between your legs allows your hips to stay closer to the center of the seesaw. Also, when your hips are externally rotated and slightly abducted, you can typically reach deeper degrees of hip flexion. (You can experiment with this by lying on your back and doing the hip-flexion flexibility test, only instead of pulling your leg straight back, pull it toward the side.)

If you can’t perform an ATG squat with these two modifications, you can try to trick your nervous system by pulling yourself into the deep squat. Too often we rely on gravity to put our bodies into the correct position, forgetting we can control ourselves.

First, pull into ankle flexion. Pull your toes to your nose and activate the muscles on the front of your shin. Second, pull into hip flexion. Contract your hip flexors, trying to pull into the squat position. You can get a sense of what this feels like by lying on your back with your feet shoulder-width apart and bringing your knees to your chest.

If you still can’t do a decent squat, you need to work on your flexibility and/or mobility. This doesn’t mean you can’t do weighted squats. Here are a few things to consider.

First, sometimes weighted squats are easier to perform than squats without weight (think about the weight’s impact on the seesaw). I did weighted squats for years even though I couldn’t do a proper square squat. HOWEVER, you’ll probably have more aches and pains if you rel on an external weight to bully you into the proper positions.

Second, you can experiment with weightlifting shoes. “Weightlifting” (one word) refers to the sport of Olympic weightlifting, which shouldn’t be confused with powerlifting. Olympic weightlifters compete in the snatch and the clean and jerk. Powerlifters compete in the squat, the bench press, and the deadlift.

Weightlifters wear shoes with flat, hard soles and elevated heels. This makes it easier to achieve a deep squat position with an upright torso for reasons you should be familiar with. (Keep in mind, weightlifters wear these shoes as an enhancement, not as a crutch. If you have insufficient flexibility and/or mobility, they’re more of a crutch.)

Third, there are plenty of leg exercises you can do that don’t require as much flexibility and mobility. You can always do these exercises until your flexibility and mobility are up to snuff.

More coming soon…