Looking against our ultimate goal of the solid base with a prime time physiology for muscle building, we have an idea of where we want to go. We want to use nutrients and energy preferentially, effectively, and most efficiently for building muscle. But this alone isn’t enough right now because of the body fat baggage. [...]

Looking against our ultimate goal of the solid base with a prime time physiology for muscle building, we have an idea of where we want to go. We want to use nutrients and energy preferentially, effectively, and most efficiently for building muscle.

But this alone isn’t enough right now because of the body fat baggage.

The good news is that growing more efficient with using nutrients and energy isn’t mutually exclusive from dropping body fat, and so we start with the overly simple opinion that body fat is nothing more than stored energy. This neglects lots of things (like the idea of stress perhaps being a promoter of fat gain), but brings about two important concepts which happen to be common in the obesity world to explain fat gain:

- Body fat is excess energy

- Body fat requires the storage gates to open

Truth be told, the precise mechanism behind fat storage is unknown, so don’t let anyone tell you otherwise. Now would be a good time to mention that the philosophy we’ve been uncovering isn’t absolute truth (as that doesn’t exist), but rather what’s worked for me and what seems to work with most of the people I deal with — it’s the strategy I fully believe to be best.

Because of the above two nuggets, the top two ways people go about losing fat (at least from what I see) is either to:

- Change energy intake so there’s no excess (by eating less)

- Change the propensity to store things (by trying to adjust insulin, the “master” storage hormone, through carbohydrate intake)

I don’t know if anyone can absolutely 100% refute the idea of body fat having some relationship with energy because it’s true at the extremes. You won’t end up fat if you eat like a bird, and you won’t end up skinny if you eat like a hippo.

But this neglects some juicy bits. There’s a problem playing the energy game.

Stimulation, stress, breakdown, and regeneration

The problem with playing the energy game is that whole stress and stimulation thing we talked about before. With strength training, we’re going through a specific kind of breakdown that needs a specific kind of buildup.

Decreasing our energy to a level below what’s needed for normal functioning doesn’t bode well for much “extra” rebuilding, but there’s also the specific bit. What builds bone is different than what builds skin is different than what builds muscle. Building back up depends on what was torn down.

As mentioned before, you can run through the macronutrients and see that carbohydrates are typically a higher intensity muscle fuel and fats are a lower intensity fuel and that proteins are typically builders (although the body does what it can to turn one thing into another in times of need). You can even dig deeper into the vitamin and mineral bucket and see that each of them support different things within the body.

Food—supply, a member of S. Island—is more than a number, it’s a specific set of tools to do a job our body needs to get done, and that’s usually a two pronged process. One is the energy (calories), the other is the nutrients.

A look at body fat and supply

It’s very easy to be over on energy if you don’t have any nutrients to make use of. Two workers is too many if you only have one screwdriver. But if you have five screwdrivers? Then you can get away with more workers.

This is why, in my opinion, eating wholesome and unprocessed foods are better than eating processed nutrient void foods. Eating nutrient dense foods has both the energy and the tools.

So you can play the thermogenic game and ignore everything else by calories if you really wanted to. You can drop calories to the floor, but you have to think (at least, I think) that it’s really easy to go over on calories that way. There’s a chance that by thinking about more than energy you can eat more and still be using less energy than you need.

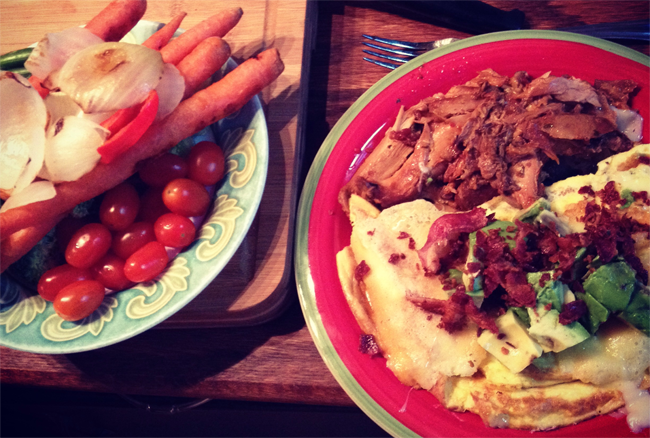

A secondary downside to focusing more on energy and less about nutrients is that it makes repairs from the stressors tougher. Broccoli and steak is going to do a much better job at handling some kind of muscle repair than a “portion controlled” helping of lady locks. And who knows. You might even be able to eat more steak and broccoli because it’s both energy and nutrients, and those nutrients are going to be keeping your body kicking behind the scenes with repair and rebuilding.

Beyond that we have two other concerns:

- Doing this in a way that might benefit muscle building down the road (uptake)

- Doing this in a way that doesn’t totally neglect our specific stress

To this, we turn to insulin and carbohydrates.

Insulin, carbohydrate intake, and fat gain

If calories in vs. calories out (CICO) is the numero uno reductionist fat loss strategy, then a low carbohydrate diet is numero dos. Some people say that it’s not necessarily about incoming energy, but rather your body’s propensity to store the energy away.

This storage is mediated by a lot of things but usually get’s dumped on the shoulders of a hormone known as insulin. To see why, all you have to look is look at a diabetic with dysfunctional insulin. No insulin = no uptake = stuff getting gunked up in the blood = thick blood = bad news.

Some feel that insulin is the devil. That’s non-sense because no one wants diabetes. Insulin is necessary for any sorts of storage, and this includes storage within the muscle. It’s absolutely necessary to stimulate insulin in some capacity for muscle growth. As for the macronutrients that have the most play with insulin?

Starchy carbohydrates.

(You might be reminded of the Glycemic Index here, but use Glycemic Load instead. It’s also worth mentioning that some proteins also have play with insulin.)

As this all relates to fat loss: there’s a relatively strong relationship between body fat and insulin resistance. Cells don’t respond well to insulin, which makes it tough to store things, which makes the body produce more insulin (when somebody isn’t listening, one solution is to yell louder), which makes it even tougher to make use of any sorts of stored energy.

Not only does insulin resistances make for bad fat loss, but it also makes for poor muscle gain as part of the process is rebuilding and repairing and restocking what was depleted.

And so the theory here goes that adding even more insulin into the mix by tanking a bunch of starchy carbohydrates will add even more muck to the messy soup that’s brewing, and that it’s best to have a lower carbohydrate intake if your goal is fat loss.

Alice, which was to I ought to go?

If you couldn’t tell, we’ve backed ourselves into a nifty corner. We started with this idea of monitoring energy intake as a whole, but also taking note of the tools we’re giving the energy to work with. We then moved to a second idea in carbohydrate intake and insulin sensitivity — perhaps keeping carb intake lower for fat loss.

But we’re forgetting about something aren’t we?

The stress.

We’ve made a point out of strength training the right way early on in order to get our muscle churning. Part of this will likely be glycogen depletion (the severity of which depends how exactly you train), which means carbohydrates can be a useful fuel.

Clearly we have work to do. A lot of work. We just peeled off the first layer of settled wax with this essay, so think of it as an introduction and not any sort of prescription. We’ll continue to develop from here, but if you haven’t already done it: start with relatively unprocessed nutrient dense foods. That alone can do great things for you.