It’s 11PM. You kiss your wife on the cheek and say good night. Lights off, you nestle your cheek into your pillow. Your body sinks into your mattress as you exhale from a deep breath. Your eyes close. Sleep awaits. Two minutes later your ears awaken. There’s a sound. Your eyes jut open but you [...]

It’s 11PM. You kiss your wife on the cheek and say good night. Lights off, you nestle your cheek into your pillow. Your body sinks into your mattress as you exhale from a deep breath. Your eyes close. Sleep awaits.

Two minutes later your ears awaken. There’s a sound. Your eyes jut open but you lay motionless, diverting all resources to your hearing. Is it the front door? Someone trying to break in?

You hear it again. The front door knob is jiggling. This is it. Your nightmare come to life—the stuff that you thought only happened in movies.

As your heart rate and breathing quicken, blood rushes through the body faster than you sloshed through the waterslide at the water park last year. “This is it,” you say to yourself, as you look around the room searching for something to use as a weapon to defend your turf.

Or . . . not.

Because maybe when you hear the sound at the front door, you sink further into relaxation. You sleep easier knowing that your twenty-one year old son that went over a sketchy friend’s house for a party returned home safely.

In each situation, the stimulus—the signal—is the same. But the response is different. All stimuli might be equal, but the response to them is anything but.

This is context.

The universality of function assumption

Let’s call it the universality of function assumption. It’s the idea that we all react and respond to all things the same. As you can see though, we don’t even react and respond to things universally within ourselves let alone between each other.

Something as simple as perception makes all the difference, let alone how your guts and innards decide to respond (ironically enough, this partly depends on perception too). This is why I harp on sight beyond sight and the pursuit of Quality. (I know I sound like a deranged philosopher, but that’s probably an accurate representation.)

It’s troubling. We like universality because uncertainty is scary. We want to know if something is bad, and we want to know that it will be bad from now until the end of time . . . for all of us. Unfortunately, save for poison, this doesn’t often work because it neglects context.

- Eggs are 100% bad all the time.

- Sugar is 100% bad all the time.

- Sitting is 100% bad all the time.

- Aerobic training is 100% bad all the time.

We’re quick to say something is so without any exceptions. This, I think, has done more harm than good because it always neglects the big picture of certain things being something under a specific context.

Sitting is killing us. Right. I get it. But you know what isn’t helping? Most people that sit a lot hate their job, commute through pollutants, have (probably) more stress, have break rooms filled with jelly donuts, and probably have less time to shop, cook, and prepare quality meals. Something tells me — something — that this sitting thing would be different if we all sat in front of beautiful scenery in nature without a care in the world.

There always is a bigger picture. There’s always emergence.

There’s always culture. There’s always context.

It doesn’t make sense

We can run down the list of things that have us scratching our heads forever.

- Some people, like the Okinawan’s, do just fine on high carbohydrate diets. Others, like the Inuit Eskimo’s, do just fine on a high fat diet. And by “just fine,” I mean that they’ll both probably live healthier lives than anyone reading this.

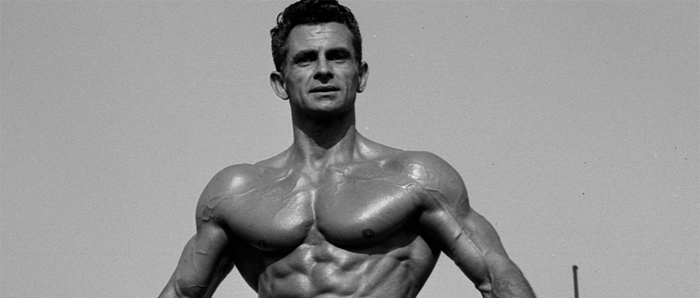

- Some people, like sumo wrestlers, use intermittent fasting to get fat. Others, like me, use it to look good naked.

- Some people, like Vince Gironda, recommended a low carbohydrate diet to stay lean and grow muscles. Others, like Chinese Olympic weightlifters (who are lean in lower weight classes), chow down on rice to get strong.*

What’s right? What’s wrong?

Better yet, what does the research say in all of this?

That’s a good question because research is often context-less, and we (including myself) often assume context. We can pour in dozens of papers on carbohydrate intake, glucose, and insulin sensitivity . . . as it pertains to those already metabolically damaged, those on the verge of being metabolically damaged, the obese, rats, and people that probably aren’t out to actively enjoy living a life of physical manipulation.

(There goes that perceptual bit again. Someone that sees eating vegetables and avoiding cake as a stressor is going to have a different life than someone that sees it as comfortable and rewarding. I think sensation and perception are things often missed, but that’s a tale for another day.)

But what does that say about us?

What a nut says about context

There’s context in everything, and I could write a billion word rant about this. (I did, actually. But for both of our sake, I deleted it.) Context makes a lot of information out there less than perfect.

But that doesn’t mean we should ignore it 100%, just like it doesn’t mean we should believe it 100%.

I think it can be best understood by a quote from The Wise Man’s Fear by Patrick Rothfuss:

“A story is like a nut,” Vashet said. “A fool will swallow it whole and choke. A fool will throw it away, thinking it of little worth.” She smiled. “But a wise woman finds a way to crack the shell and eat the meat inside.”

There’s some meat inside of just about everything.

And this is why I have to talk to you about cookies. Cookies will explain it all better than I can. But not now. I think you’ve had enough for now. Cookies are for next time. Just know that context exists, and it’s kind of a big deal.

But cookies will bring it all together. Supply. Stimulation. Signaling. Soul. S. Island. All of it.

In cookies.