We are energy consuming and beings, and thus we live under the laws of thermodynamics. Energy can’t be created or destroyed. To lose weight, you must use more energy that you consume. To gain weight, you must consume more energy than you use. The mainstream story we’ve been told—the one supposed to cure all of our [...]

We are energy consuming and beings, and thus we live under the laws of thermodynamics. Energy can’t be created or destroyed. To lose weight, you must use more energy that you consume. To gain weight, you must consume more energy than you use.

The mainstream story we’ve been told—the one supposed to cure all of our body composition woes—is to eat less and exercise more. This turns into a game of energy balance. You’re either (-) and you win, or (+) and you lose.

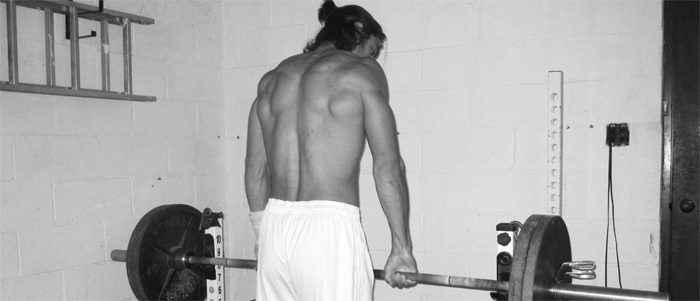

Now, I got beef with some (not all) of this story, which will all be cooked with time. But one of the reasons I’m not all in with the thermogenic game is because, to me, it’s an overly simplified picture that really only applies to people that want to lose “weight.” (If your ambitions include being more muscular than you are now with a lower body fat than you have now, consider a different perspective.) It says: eat (+) 500 and you’ll look like this, as if every human being that eats a specific # of calories over their allotment ends up with the same build.

This ignores the body being smart enough to delegate its resources to areas of need. Meatheads have big biceps and pecs because they tell the body the muscle tissue there is more important than rest. The body is smart enough to handle this specific sort of stress and adaptation.

(Now would be a good time to plug Taleb’s concept of antifragility, as I think it’s a great way to envision the body’s adaptation skills that pay the bills.) What you experience goes a long way in creating who you are. Get injected with a bit of a pathogen, and you adapt specifically to that pathogen.)

Even though we’re all humans and all made up the same stuff inside, that stuff can change based on current need and perceived future need.

Calories and nutrients are universal, but how you body makes use of them isn’t.

These “points of need” are what I like to call flinches — patterns that the body settles into because it thinks its better off with them than without them. And they work themselves into normal function for efficiency.

In other words, it’s possible to coax your physiology to function a certain way. It’s possible to change the flinches.

To understand how, let’s get sssssssssssssssssssssssssssizzling.

Kelly Bagget’s 3 S’s to muscle growth

In order to explain muscle growth, Kelly Baggett talks about stimulation, supply, and signaling. To this list, I add soul.

Stimulation is the way you train—what you expose your body to. This would be like injecting yourself with a specific pathogen in the name of vaccination.

Supply is what you give your body in terms of energy and nutrients for your functions. Your body prefers specific nutrients for certain jobs, but is smart enough to know how to create things its absolutely going to need in order to survive under less-than-ideal circumstances.

Signaling is your body doing the dirty work to recognize and put into action the “next” steps inside of the body. In other words, injecting yourself with a pathogen (stimulation) for a vaccine doesn’t work unless your body recognizes the danger and kicks the immune system into gear (signaling).

Soul is my addition to this mix because, let’s face it: there are 24 hours in a day. If you train for two hours, four days per week (something considered to be “a lot” by many), that’s 8 hours in one week. Considering there are 168 hours in one week, you’re looking at 160 hours of “stuff” floating around in the ether of unknown. Soul accounts for things like stress, sleep, and lifestyle—the forgotten 160.

Soul should be a no-brainer though. Take two people with the same “everything else.” One sleeps eight hours every night, takes a two hour nap every day, has a brotherly relationship with friends, and is generally happy. The other sleeps four hours, hates his job, hates his commute, has no friends, feels alone, is and is generally stressed.

Do the math in your head—that’s soul.

Rewiring the flinch

I believe it’s possible to change signaling over time. With stimulation, supply, and soul, it’s possible to rewire your flinches.

The skinny-fat flinch can be summed up by the body seeing more need for fat tissue rather than muscle tissue. End result being that the fat cells get more love.

The problem with a lot of people that struggle, I think, is that instead of thinking in terms of rewiring the flinch, they instead play the thermogenic calorie game. But the thermogenic calorie game doesn’t change how your body functions.

If you flinch when something is thrown at your head, one way to avoid the flinch is to avoid anything being thrown at your head. This to me is the calorie game.

Don’t change how the body functions, just give it less to function with.

Sure, you can go low calorie and lose weight and all that jazz. But for the rest of your days you’re always going to struggle keeping the weight off because your body hasn’t really changed. You still flinch the same way, and your body always wants to return to where it was before.

(A quick aside here: when you deplete fat cells for all their worth, by laws of negative feedback loops, there’s a good chance they want to fill right back up again. The body did all that work amassing junk to use in case of an energy crisis, you went through that crisis, so the next logical thing for the body to think: restore! At least, that’s what I think. The body is smarter than me though, you make your own judgments.)

The other way is to rewire the flinch. To let the fear bleed out. Change stimulation, supply, and soul in a way forces signaling to change.

Is signaling out of your control?

We’re trying to rewire the flinch by changing stimulation, supply, and soul. But the problem is that signaling seems out of our control. After all, you can give yourself a small dose of a pathogen for a vaccination, eat to fuel your recovery, and be absolute soulicious, and yet if your immune system doesn’t kick into gear, nothing happens.

Put this way, it seems that signaling is not only the most important S, but also out of our control. And sometimes it is.

Some have great genetics and naturally signal for muscle retention and growth—even on a lower calorie intake. For whatever reason, their body prioritizes their muscles. I used to help out with the sports teams (primarily football) at a Division I college. I know the power of genetics, and I also know of many genetic freaks.

In fact, one kid (now in the NFL) ate so little food, that we gave him the most sugary-calorie filled weight gainer to help him gain weight. And you can bet he had decent enough amount of muscle on him as is despite his shady intake.

And here’s one of my favorite quotes from running back Adrian Peterson:

“This is also a matter of genetics. Look at my dad. And my mom’s side, my aunts and uncles, they’re all ripped. At 50 years old, they’ve got six packs and eight packs. My body just heals differently. I know it has a lot to do with rehabilitation and work ethic, but I really credit my genetics for my recovery as much as anything else.”

But I also know the power of work. Hard work. In The Sports Gene, David Epstein writes about two high jumpers: Stefan Holm and Donald Thomas. Holm, despite being a dwarf in the field of high jumping, was able to scratch and claw his way to a gold medal (even to the point of his jumping tendon thickening fourfold). He spent tremendous time training the high jump and refining the technique.

In contrast, Thomas didn’t. He had no previous training, was said to have awful technique, and started winning from the get-go. He even beat Holm in the 2007 World Championship.

And might I add, Holm won a gold medal. Thomas didn’t.

Nature, nurture, and the flinch

The examples between nature and nurture run amok, and it’s always a point of contention. Some are quick to blame terrible genetics and throw in the towel. I have fat cells, they don’t. They barely train and have muscle, I don’t. It’s hopeless.

Recognizing these differences are important. From my experience, the last thing you should do is ignore them. But you can’t hinge your existence on them. In general, the 10,000 rule is the gold standard for time to expertise.*

*(Of course, it’s not 10,000 on the dot. It’s really just to say that people are rarely prodigies, and when you amass the body of work people at the top of the pyramid have put it, it tends to add up more than people want to admit.)

I started moving my body in 2001 with tricking. In 2006, I started to strength train. It probably wasn’t until 2011 that I felt like I had a firmer grasp on my body. In fact, in April 2011, I would have told you that gaining muscle without getting fat was impossible.

In 2012, things changed more towards the “I think I know what I’m doing” side, but I still don’t know what I’m doing, really.

I don’t how it all works, I just know what has worked for me.

I’d hesitate to say I have 10,000 hours of solid practice under my belt. Many of those years weren’t “practice,” they were expeditions. I didn’t know what I was doing, and so I had no system of corrections or any way to make practice meaningful — there’s a difference between mindlessly going through the motions and deliberate practice.

This is where the value of a coach comes in and is also something to think about. Most people at the top have a coach. Tiger Woods has a coach. This helps not only with their skill, but it starts them off in a better place. They start amassing those 10,000 hours fast. From the get-go they know what’s good and bad so they can correct and play from a good baseline.

Most people that try fixing their body don’t know good. They go on the Internet, read about some garbage, try it out brainlessly, and then quit. That’s not practice; it’s masturbation.

In general, I’ll let you deal the genetic hand of excuses to me if you can confidently say that you’ve done 90% of the things right for ten years and have zero results to show for your work. Adding to this, you were enough of a goonie to push your limits at times.

So let’s focus on the 4 S’s and rewiring your body.

The most important S for rewiring yourself

By laws of emergence, stimulation, supply, and soul—everything you do—plays a part in the signaling-flinch rewiring process. This makes it a gooey world and can lead to many mental breakdowns (been there).

There’s a good chance you’ve fixed one (or even a piece) of these S’s, only to be sabotaged by another piece. There’s no need for another example here: go back and revisit the one given at first mention of soul.

Everything is important, no doubt. But I think that there might be one S that’s more important than the rest — one S (that isn’t signaling) that rules them all.

+++++