When I was fourteen I cared about three things: Mountain Dew Code Red, Andy Capp’s Hot Fries, and Dragonball Z. That was, until I stumbled upon tricking and developed a virtual idolization for a guy known as “Jujimufu.” So when Jujimufu developed an interested in human performance, I developed an interest in human performance. And [...]

When I was fourteen I cared about three things: Mountain Dew Code Red, Andy Capp’s Hot Fries, and Dragonball Z. That was, until I stumbled upon tricking and developed a virtual idolization for a guy known as “Jujimufu.” So when Jujimufu developed an interested in human performance, I developed an interest in human performance. And the rest is history.

When I was fourteen I cared about three things: Mountain Dew Code Red, Andy Capp’s Hot Fries, and Dragonball Z. That was, until I stumbled upon tricking and developed a virtual idolization for a guy known as “Jujimufu.” So when Jujimufu developed an interested in human performance, I developed an interest in human performance. And the rest is history.

This article wasn’t in the original plans for the Solutions for the Skinny Fat Ectomorph series. But a lot of skinny-fat information has popped up since I wrote 11 Training Tips for the Skinny Fat Ectomorph. And if there’s one thing everyone must know, it’s that you can’t really take advice from someone that has never sat in the skinny-fat shoes. My apologies go to those that just want a routine and nutrition plan. But you will be better served in the long run.

The Past and the Future

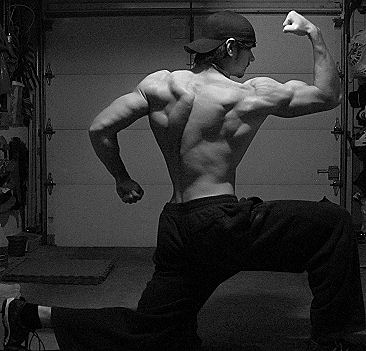

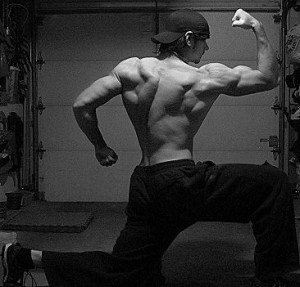

Everyone neglects the past. I could have just posted my pictures and listed my training program and have been done with it. But the way I train now isn’t the same way I trained to get where I am. Training history matters. So I’m adding this piece for two reasons. First, so you can see that I was once a member of the Skinny Fat Ectomorph Brohirrim, which, by the way, is now the official name of the skinny-fat tribe. (Yeah, I just made it up. And it’s a super nerdy reference to Lord of the Rings too. Awesome.) Second, so you can see my evolution alongside what worked and what failed. Now, I don’t remember everything from the past six years. But what I do remember follows.

February 2006

I decided to “get serious” on February 16, 2006. I know the exact date because I so aptly dated the folder for the pictures. (Too bad I didn’t follow through with this smart strategy.) As you can see, typical skinny fat ectomorph body type. No arms. Most of the body fat chucked around the waist. Good times. I think I was 200 pounds.

June 2006

Over the next five months, I jacked my physical activity through the roof. I lifted weights, but not seriously. My routine consisted of mostly isolation exercises as I didn’t have good equipment — just a cheap bench, barbell, and adjustable dumbbells. So I did what I could, but it wasn’t ideal.

To aid fat loss, I downed instant coffee in the morning (even though I hated coffee) and did “cardio” on an empty stomach as that was what cool kids did back then. Exercising on an empty stomach was reported to better utilize fat for energy, and caffeine encouraged the same. So three days per week, rain or shine, I did tabata sprints. The other days I walked on the treadmill for forty five minutes.

I devoutly ate six meals per day. It was clockwork. Breakfast was one serving of oats and two eggs. Lunch was one piece of whole wheat bread, one can of tuna, and one piece of fruit. I can’t remember the other meals, but that slice of bread at lunch was the last of the complex carbohydrates. I shot for six meals at 300 kcals, which brought me to 1800 kcals.

October 2006

I dropped the”cardio” and closely monitored my nutrition. Although I put more emphasis on weight training, I wasn’t gaining muscle fast enough for my liking. So I listened to conventional wisdom and I “bulked.”

It was a bad decision.

But I did upgrade my equipment. I now had squat stands and Olympic sized plates and barbells.

February 2007

I ate my way to 203lbs, and the results didn’t show. My arms remained rails, and body fat crept to my midsection faster than muscle elsewhere. Looking back, I’m sure I did one million things wrong. But as a whole, my first bulk didn’t go well. Am I biased? Yes. But only because my greatest gains (as shown below) came when I trained without the “bulk” mentality.

Late 2007

Bulking taught me one thing: I knew how to get lean. And fast. I knew what my body responded to, so it came down to execution. By summer, the extra weight was gone and I was back to training and eating normally. Although I intentionally kept my body fat “low,” I didn’t obsess over a “six pack.”

My routine (created by my then mentor Chicanerous) went something like this:

Sunday: Back Squats 6×6, Good Mornings 2×20, Press, Chin-ups

Wednesday: Back Squats 5×3, Romanian Deadlifts 5×5, Press, Dumbbell Row

Friday: Bulgarian Split Squats 3×8, Cleans, …?

Saturday: Ultimate Frisbee games

But after consistently failing to respect recovery, I was bound to break. And one day, during an Ultimate Frisbee match, my groin exploded. It took six months to heal. Upper body lifting became lax, and I lost nearly everything I had built. Before the injury, I squatted 380 for reps and I romanian deadlifted 315 for reps. But after the injury, my strength was gone.

http://youtu.be/qxJ8PHXqis4

2008

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AQ6_1QM9d4Y

After healing, I went on Starting Strength. My squat and deadlift strength prospered. My upper body strength, well, not so much. And I was stricken with intensive bouts of chronic knee pain. Idiotically, I ignored the pain. Eventually settling into the Texas Method, I adopted the whole “isolation exercises are garbage” mentality. My lower body got stronger, and I played to what I was good at. It’s no wonder I wasn’t satisfied with my physique. As a small aside, this was the year I started working with athletes. And as a note, I bulked in 2008 for a month or two. Results were lackluster. But it did reaffirm my ability to lose fat after a “bulk.”

2009

In January 2009, I felt the Texas Method wasn’t ideal for hypertrophy. Once again, I decided to bulk. My program was WS4SB, and I ate my way 233. It was the heaviest I had ever weighed and the heaviest I have ever weighed. But my bulk failed again. The hidden benefit of bulking for three straight years and failing for three straight years is that I became a master of losing fat. (Holding true to this day.)

Another bout of chronic knee pain forced me to stop squatting. On top of that, the constant maxing on WS4SB made my bench stall fast. And my joints weren’t too happy either. But I was “bulking,” and I thought eating more would solve my problems. It, of course, didn’t. I ate clean though. Tons of eggs, oats, brown rice, and the usual fare. But it didn’t matter.

My knowledge of health, fitness, and training was at an all time high. I could write programs for anyone except myself. For whatever reason, I thought I followed different rules and tried to follow a “standard” program. Eventually, my injuries forced me to rethink my path. Midway through 2009, I stopped lifting. For the rest of the year, and for first few months of 2010, I dedicated my time to fixing my chronic knee pain.

2010

http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=Yo1D7sJ1BcA

http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=qA5sBLhqAuw

2010 was a great year. I was healthy and doing better than ever. I was getting strong, I was tricking regularly, and I finally “got it.” My schedule was a little funky, but I enjoyed it. Wake up was at 5AM-6AM. Breakfast was oats and eggs. I worked from 7AM-3PM. Lunch was a piece of fruit at 12PM. And when I got home at 3PM, I lifted. Two or three meals followed. Of what though, I can’t remember.

Early 2011

http://youtu.be/kkSppZUNfjA

On January 28th, 2011, I broke my foot in five places. It was frustrating. For the first time in my life I was healthy. Things were perfect. But this, I thought, was the nail. The end.

From February to mid-March, I was on crutches. I began my rehab process early (I’m not a fan of traditional rehabilitation timetables and theories). I was doing supported squats in my cast three weeks post injury. One week before getting my cast off, I was walking with a boot. It didn’t matter much though because when I got out of my cast my foot was lifeless. I had a severe limp. Walking on it was more painful than breaking it. But it felt good to be free.

From February to mid-March, I was on crutches. I began my rehab process early (I’m not a fan of traditional rehabilitation timetables and theories). I was doing supported squats in my cast three weeks post injury. One week before getting my cast off, I was walking with a boot. It didn’t matter much though because when I got out of my cast my foot was lifeless. I had a severe limp. Walking on it was more painful than breaking it. But it felt good to be free.

What’s ironic is that this what began my intermittent fasting journey. Before breaking my foot, I loved breakfast and never went without it. But after breaking my foot, standing for more than five minutes made my foot would swell inside of my cast. That, and being on crutches, made cooking rather impossible. So I learned how to survive without breakfast, eventually adopting the principles of intermittent fasting.

I’ve always believed you can learn from negative experiences. So I forced myself to extrapolate the good out of breaking my foot. The injury taught me that health is king. Over strength. Over muscles. Over everything. If you’re not healthy, why does it matter? It also taught me patience. Things don’t happen over night. Ever. So when I started training again, I didn’t care about adding weight to the bar. I didn’t obsess over strength. I just enjoyed being able to train.

Eventually, I got some squat strength back. But then it hit me: what the hell was I doing? I broke my foot, yet I was putting a loaded bar on my back and tentatively teetering out of a rack. It just wasn’t worth it anymore. So I stopped doing it. Yes, I stopped squatting.

Then I asked myself: what do I love doing? And when I answered, I acted. For the next few months I lifted everyday. I thought my foot could benefit from a low load and a high frequency. So I did deadlifts, power curls, hip thrusts, unilateral dumbbell floor presses, and waiters walks. Concurrently, I did Chat Waterbury’s PLP program.

I felt great every day. I left the gym refreshed. It was perfect. And it was just what I needed.

This taught me a few things. First, recovery doesn’t happen in a 48 hours. Recovery depends on the stress imposed on the body in relation to the current state of adaptation. I, of course, already knew this. But I never felt it. I was feeling it. Second, stress is more than strength. While never adding weight to the bar, I was filling out because my volume and frequency — not intensity — were increasing. I can’t remember the totality of my food intake but it looked something like six eggs, a pound of turkey meat, and a ton of vegetables.

I sprinted twice a week most weeks. Usually eight to ten sets of fifty yard sprints on a hill. Nothing big. Certainly no cardio fest. I just sprinted up the hill, walked back down the hill, hung out, and then went again when I felt good.

Really, I just stopped obsessing. I didn’t care about maximizing muscle growth. I just did what seemed right. And what seemed right was training easy every day, doing a lot of body weight stuff, and sprinting. But it was perfect because I didn’t care about aesthetics anymore. Moving without pain became my primary objective.

So for the entire summer I lived stress free, lifted some heavy things, and sprinted. Most importantly, I stopped obsessing. Not once did I come close to failing, busting an adrenal glad, or thinking about changing programs. I lifted every day because I felt great every day. I might have gotten more muscular. I might not have. But I didn’t care to take notice. And I truly think this is what allowed me to make progress — the lack of obsession.

Now, I’m reluctant to say this because a lot of people are going to combine the 40 Day Program with PLP and expect huge gains. Not that it doesn’t work, but idly following my path is dysfunctional thinking. And if you don’t know why, you don’t “get it” yet. The actual “program” doesn’t matter as long as it suits your goals — an idea that sounds contradictory as the next article will suggest programs. But, in general, most people will be awesomely served doing the following:

- Lifting weights consistently

- Mastering body weight exercises

- Sprinting

- Eating primarily meat, fish, eggs, and vegetables

And really, has that ever not been the formula? You don’t have to kill yourself in the gym. You just don’t. You need to stay healthy enough to lift consistently. That’s it. And by consistently, I don’t mean training daily. I mean training regularly for a few years. No one that trains regularly becomes weaker and less muscled. So as long as you’re consistent, you’re on the right path. Look at my life. I didn’t get here with one program. I got here because I found ways to consistently train — through injuries and downturns — for six years. I didn’t just hop on an eight week program and ride it to success. And you shouldn’t expect to either.

+++++

Other articles in the series:

- Solutions for the Skinny-Fat Ecto, Part I – The Basics

- Solutions for the Skinny-Fat Ecto, Part III – Training

- Solutions for the Skinny-Fat Ecto, Part IV – Nutrition

=====

Accompanying resource: The Skinny-Fat Solution