Give up. Quit now. Stop. You’re stuck with the abilities you have now for the rest of your life. If you aren’t good, you’ll never be good. Greatness is born, not earned. You can’t improve. Ever. The born with – stuck with mentality was the commanding consensus on both skill and ability for a long time. The script has [...]

Give up. Quit now. Stop. You’re stuck with the abilities you have now for the rest of your life. If you aren’t good, you’ll never be good. Greatness is born, not earned. You can’t improve. Ever.

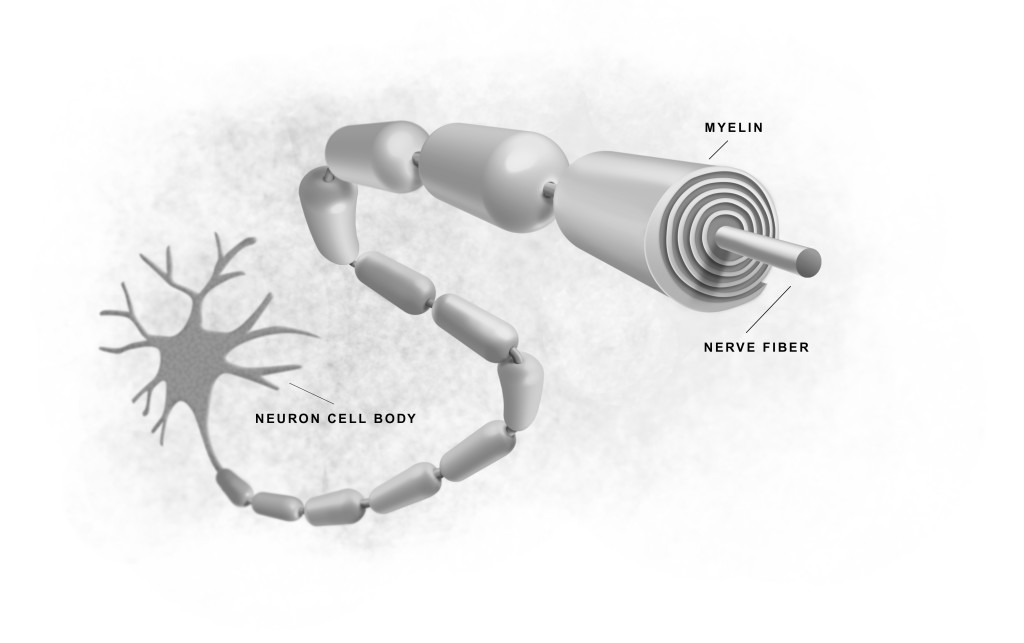

The born with – stuck with mentality was the commanding consensus on both skill and ability for a long time. The script has been flipped thanks to the discovery of myelin.

Greatness may not be born at all, but rather learned over time with a certain kind of practice.

If you aren’t good, you simply need to make yourself better.

How?

By developing the skill.

By practicing the skill.

Drive to the grocery store

You’re at your house and you need to get to the store. There are a lot of routes you can take, but that doesn’t matter. What matters is that you pick one and you take it.

You take that road over and over and over. You get better and better and better driving that specific road. You know how to cut the corners, turn the wheel precisely around the bends, and barely stop at the stop signs where police don’t sit.

This is myelination.

(1) Every human movement, thought, or feeling is a precisely timed electrical signal traveling through a chain of neurons—a circuit of nerve fibers. (2) Myelin is the insulation that wraps these nerve fibers and increases signal strength, speed, and accuracy. (3) The more we fire a particular circuit, the more myelin optimizes that circuit, and the stronger, faster, and more fluent our movements and thoughts become.

-Daniel Coyle, The Talent Code

Movement is a precisely times sequence of electrical signals sent throughout your body through your nerve fibers. They take a specific route that you tell them to take. Your body optimizes this route with insulation. More insulation makes for faster signal travel.

So skill? It’s all about you insulating the right pathway.

What is a skill…?

Everything is a skill. Moving your finger is a skill. Squatting is a skill. Pressing is a skill. Putting is a skill. Throwing is a skill. Gripping is a skill.

Simple skills are packaged together to create complex skills, but it’s still all about precisely timed electrical signals. Doesn’t matter if it’s simple or complex.

We often take the idea of a “skill” for granted, seeing only what we can’t do or what’s tough to do as skill.

Consider holding a pen and writing a sentence. This is a complex skill. Most wouldn’t even think of it as a skill at all though. We’re taught how to do it when we’re young ,and we repeat it so many times that it becomes easy.

That’s really the sauce of skill though: taking something complex and wiring it into your system so deeply that it becomes an unconscious happening.

As Daniel Coyle writes, in The Talent Code — the definitive book on myelination and skill — myelin doesn’t care about who you are, it cares about what you do. (By the way, every human being needs to read The Talent Code. Follow it up with The Sports Gene for the other side of the story.)

This is good because we can go from scrappy kids that can barely hold a pencil to older (still probably scrappy) kids that can form sentences and create artwork with the same pencil

The downside of myelin?

It’s good that myelin only cares about what you do.

But it’s also bad.

Because myelin doesn’t recognize correctness, it just insulates the pathway.

You’re at the top of a ski slope with nothing but fresh powder below you. The path you take is your poison…until one is created. Once you create a path, your skis unconsciously follow the formed grooves. With every run, the path gets optimized.

This is good, right?

Absolutely…

…if you took the right path from the start.

If you didn’t? If you took the most off beaten, longest travelling, totally askew pathway? Myelin doesn’t care; it only knows what you do.

Myelin isn’t going to create the best path, it’s only going to optimize the path frequently traveled.

Practice only makes perfect if you’re practicing perfectly. Practice simply makes permanent. The only kind of practice that makes perfect, as the old adage goes, is perfect practice.

This is big because your body isn’t an Etch A Sketch. You can’t just shake yourself into a clean slate.

Myelin wraps, it doesn’t unwrap.

The grooves you make down the ski slope are there to stay. If you don’t groove the right pathway, it’s extremely tough to learn a new pathway. This is why motor repatterning requires immense volume and time. (As those of you that have my knee pain book know.)

As Buddy Morris once said:

“It takes 500 hours to invoke a motor pattern before it becomes unconscious. It takes 25-30 thousand reps to break a bad motor pattern.”

– Buddy Morris

If this doesn’t make you skittish about practice, I don’t know what will. It makes me scared. I don’t want to ingrain any bad patterns. You shouldn’t either. But ingraining bad patterns isn’t the same thing as making mistakes.

Make mistakes…small ones

Skill is about building a pathway. You don’t want a bad pathway, but you have to reach. Perfect practice makes perfect, but that doesn’t equate to consistent absolute perfection.

Perfect practice is all about the sweet spot.

“The sweet spot: that productive, uncomfortable terrain located just beyond our current abilities, where our reach exceeds our grasp. Deep practice is not simply about struggling; it’s about seeking a particular struggle, which involves a cycle of distinct actions.”

-Daniel Coyle, The Talent Code

There’s a range. You want to reach, but you don’t want to reach too far. When you can juggle two balls, you try to juggle three. Not fifty. Trying to juggle fifty would only confuse. It’s too far beyond the sweet spot.

“The trick is to choose a goal just beyond your present abilities; to target the struggle. Thrashing blindly doesn’t help. Reaching does.”

-Daniel Coyle, The Talent Code

And while moving from two to three balls, you shouldn’t expect absolute perfection. You’ll screw up, but that’s what learning is about: making small mistakes, recognizing the mistakes, and then fixing them. Sound like antifragility, no?

Practice makes permanent, not perfect. Only perfect practice makes perfect. But perfect practice doesn’t mean perfection.

This blows my mind, will it blow yours?

Skill is my baby. I could read book after book on how the body wires itself. I don’t know whether it comes from tricking or being a general physical-personal upgrade junkie.

A deep appreciation births for what your body is capable of when you understand just how intricate skill development is. Skill is complex. Skill is a biological phenomenon.

It’s not only about insulating, but also timing. Timing is vital because neurons are binary: either they fire or they don’t.

“Fields had me imagine a skill circuit where two neurons have to combine their impulses to make a third high-threshold neuron fire—for, say, a golf swing. But here’s the catch: in order to combine properly, those two incoming impulses must arrive at nearly exactly the same time—sort of like two small people running at a heavy door to push it open. That required time window turns out to be about 4 miliseconds, or about half the time it takes a bee to flap its wings once.”

-Daniel Coyle, The Talent Code

I’m giddy just thinking about the precision our body has. And I’m also giddy about the complexity. Skills aren’t binary like neurons.

Psychological arousal can kill skill. You’ve probably heard of the difference between gamers and non-gamers. Non-gamers are heroes during practice, yet can’t turn it on during the game itself. Why? Because their skill isn’t tuned to work alongside the high physiological arousal of competition.

During practice you can be lazy and relaxed. Your heart rate is lower. There’s no pressure. Your body works differently in that kind of environment.

Same goes for scenery. I’m sure many tricksters agree that scenery matters. If you learn a trick at a park always facing a certain kind of backdrop, when you move away from that backdrop you won’t be as confident.

There’s more here. I could go on forever, but I’ll spare you the time.

Realize the joy of having a body

You’re a transformer. You’re piecing yourself together. You’re plugging wires into sockets and then enhancing the connection between your pieces. Neurons that fire together wire together. What gets taxed gets waxed.

“Traditional theory said that hardware was a limit. But if people are able to transform the mechanism that mediates performance by training, then we’re in an entirely new space. This is a biological system, not a computer. It can construct itself.”

-Ericsson in T Code

Reading about skill is one thing. So is admiring skill. ESPN’s Body issue came out recently, and I’m transfixed. It’s amazing to see how the body’s of different athletes look knowing that, underneath the hood, the wiring has some sort of influence on the output. It’s fascinating.

But do yourself a favor.

Don’t just gawk. Go. Maybe it’s time to start adding rolls to your training. Maybe it’s time to go play the violin.

It won’t always be easy. According to Coyle, “The best way to build a good circuit is to fire it, attend to mistakes, then fire it again, over and over. Struggle is not an option: it’s a biological requirement.”

Expect the struggle. It’s what gives you strength.

Go lay some myelin down in your own body.

+++++

Photo credit: ski slope