I’m going to preface this post by saying that I don’t quite know what the hell I’m talking about. Of course, I have a semblance of knowledge, but most of this is hypothetical on my part. But because of my tricking days, I’ve developed a rash of noises—pops, clicks, and snaps—that emanate from my hip. [...]

I’m going to preface this post by saying that I don’t quite know what the hell I’m talking about. Of course, I have a semblance of knowledge, but most of this is hypothetical on my part.

But because of my tricking days, I’ve developed a rash of noises—pops, clicks, and snaps—that emanate from my hip. In fact, back when my two friends and I did trick, each of us would have our own signature sounding hip noises. You could tell who was warming up based solely on the depth and uniqueness of them.

The official name for this concerto is snapping hip syndrome, and it is common among tricksters and other athletes that expect their hip to have the range of motion of their shoulder. Luckily, it’s not usually painful.

The general consensus—or Wikipedia explanation—is that snapping hip syndrome is caused by a thickening of the hip tendons, which then makes it easier for them to catch on the hip’s structures. But I think there might be more to it.

And if you’re wondering why I’m throwing these ideas around, it’s because I’m not a huge fan of traditional “just accept how it is” treatment. Common protocols for snapping hip never work. They are ridiculous, actually. How can you tell a gymnast that they need to “stretch” to fix snapping hip?

Usually, people that have it are some of the most flexible athletes in the world in dancers, gymnasts, and martial artists.

Before I spill my ideas, I first have to give a bit of credit to Kelly Baggett and the Mobility WOD. The general idea of this theory was inspired by Kelly Starr and how he harps on getting the hip to sit in its capsule better, but I also borrowed some concepts from Kelly Baggett.

So, with that, as you might have guessed, my theory revolves around getting the hip to sit in its capsule better. Repeated kicking motions, or so I theorize, constantly pull the head of the femur out of its socket. As we already know, tricksters have stronger, more enlarged, hip muscles and, when combined with a femur that doesn’t sit in its socket too well, it makes it more likely to have the tendons and whatnot catch on other structures.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=57_N276-b-Y

Now, every case of snapping hip is different, so this is shotgun rehab. Nevertheless, here it goes:

Common rehabilitation strategies look directly at the problem. Usually the rectus femoris and IT band are the two tendons that catch on the bones of the pelvis. Therefore, it’s easy to think that they are the cause. But we can’t always zero in on the problem area; we have to consider all of the structures that cross the hip joint.

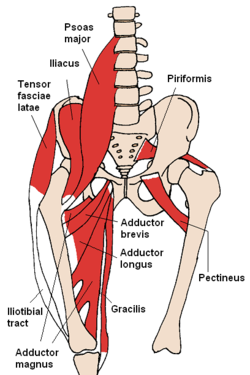

There are two muscles that often go unnoticed—the psoas major and the iliacus. They originate on the spine and pelvis and insert on the inner thigh.

Since they cross the hip joint, they have some responsibility in holding the hip in its socket (unlike most other muscles on the inside of the leg). The adductor mass doesn’t cross the hip, meaning they don’t play an as important role in hip integrity.

We also know that the deep hip flexors—according to Kelly Baggett—are usually weak in most athletes simply because they rarely do activities in which the knee is flexed above the 90 degree plane.

And while martial artists often kick much higher than that, it’s usually with the help of the body’s momentum. This is the difference between dynamic flexibility and static active flexibility. This means that it’s possible that the deep hip flexors lack the slow strength and fine motor control needed at the hip—specifically holding the femur in the socket.

So we have a few issues that are building up after just looking at the problem from an anatomical standpoint. We can attack these issues separately, but that wouldn’t get us too far because the problem is occurring in the complex kicking movement patterns. So not only do we have to treat each problem individually, but we have to think about how it can be incorporated into our kicking drills.

1) Suck your hip

I don’t know the fancy term for this exercise, but I call them hip sucks simply because to perform it you think about sucking your hip into its socket. Even though we’re mainly activating our midsection on these, we’re subliminally activating the psoas and iliacus which is tugging on the femur, encouraging it back into its socket.

(first exercises shown)

Now, when it comes to tricksters, you have to remember that my whole theory is based on doing tons of kicks with no regard for keeping the hip tight. So what I’m proposing is that all of your leg lifts and kicks need to be done with this “hip suck” implemented in order to activate the psoas and iliacus to keep the hip in its socket, but we’ll go into that a bit later.

2) Take care of the deep hip flexors

There’s a crowd out there that uses the following progression: pattern, grind, ballistic. What this means is that you have to develop endurance in a motor pattern before you can get strong in that motor patter. And once you’re strong in the motor pattern it can then be held during explosive movements.

As far as tricksters are concerned, there’s no shortage of ballistic action, but there’s definitely a shortage of pattern and grind, or, what I like to think of as slow strength. Therefore, we need to develop the slow control at the hip to get the deep hip more involved.

For this, I recommend a drill that is both explained and demonstrated by Kelly Baggett.

“A lot of people won’t be able to lift their knee an inch without squirming around all over the place. You should be able to come up several inches. The further you lean forward the harder the exercise is. I’d say if you lean forward about 45 degrees and can’t get your foot off the ground at all you could probably use some work.

I recommend doing a couple of sets of 8-10 with a 2-3 second hold at top on that exercise 2-3 x per week.”

The purpose of this exercise is to encourage the hip to be the dominant controller of the leg. This means that anytime we kick, we want our hip to drive the movement, which will create less outward tug on the femur.

3) Prevent external rotation, and the inside of the hip from collapsing

This is especially a concern for those that have lived in the front splits their entire lives. Although this demands flexibility, the rotation of the rear leg and the relaxation is the mechanism for our injury we’re trying to avoid.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LsQ1MEK9uvk

4) Deal with soft tissue and resetting the hip

I harp on external rotation of the hip being a problem. Unlike other athletes, tricksters have well developed hip external rotators from side kicking, hook kicking, and outside crescent kicking. This mean the piriformis and the other external rotators are strong enough, and potentially tight enough, to be the reason that the front of our hip—psoas and iliacus—has trouble dealing with the external rotation.

Therefore, stealing from the Mobility WOD, here are some videos that pertain to stretching the external rotators and resetting the hip.

5) Stretch the hip flexors right

Just like in tip #3, most people are used to stretching the hip flexors with front split intentions meaning that their rear leg is externally rotated. But we need to avoid that, so here are two solutions to be used during any lunge stretch.

First, internally rotate the rear leg. Second, push the hip to the outside. I dare say that both can be done, but they can. You’ll notice that you feel this stretch much more on the lateral hip and quadriceps, possibly even creeping into your psoas and iliacus.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dhPsfl9AY6U

And the combination hip flexor and quadriceps stretch can be seen at the end of this article of mine on T-Nation. Remember to internally rotate the rear leg and push the hips to the outside.

6) Incorporation of the tips into front-based kicks

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G3wTWxONF5s

7) Incorporation of the tips into side-based kicks

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aps-PbwBPQU

I know all of these tips may actually reduce your performance in some capacity. By not externally rotating your rear leg, you won’t be as flexible as you could be. You might not be able to hit the splits. You might not be able to kick as high.

At some point, however, for a trickster, you have to assess how valuable these things are. Tricking isn’t martial arts so both the splits and incredibly high kicks to the point of form breakdown aren’t absolutely necessary.

If you are a competitive martial arts athlete or gymnast, however, perhaps you will always have to suffer through snapping hip. Perhaps it’s a rigor of the sport. But for tricksters, you have the power to make your own rules. You aren’t bound by tradition. You aren’t being judged. Give these tips a shot and see how your body responds. What do you have to lose?